Evolving Idealism:

Three Decades of Change in How China’s Universities Educate Journalists

Editor’s Note: Since the late 1980s, the concept and practice of journalism in China has undergone many changes. Journalism has greatly affected every Chinese person, from the people of China, from the hoi polloi to the elites in their ivory towers. Inspired by those pioneers in the discipline, generations of students have chosen journalism as their major and career. In the beginning, it was rare for universities to have departments of journalism. Today, such departments are spawning everywhere. As society changes with shifts in politics and the economy, so also has journalism as an academic discipline. Teachers, students, and researchers of each era have chosen different paths as they navigate through the changing currents of China’s society.

The 1980s: Idealism

On May 6th, 1987, the wildfire in Daxinganling, called the Black Dragon Fire, swept through northern China. The fire lasted for almost a month. Smoke hung thick, smothering the dense forests. Fifty thousand people lost their homes, and 193 lost their lives.

Brandishing a China Youth League referral letter with the seal of the PLA Air Force Operations Department Director, China Youth Daily reporter Ye Yan and three colleagues rode a military aircraft to Qiqihar to cover the story. The journalists then took a military helicopter to Tahe, the northernmost county in Heilongjiang, China’s northernmost province.

In the planning meeting, the paper's editors and reporters vowed that this time they would forgo the usual house style which "reports catastrophes as triumphs of Communism." Their coverage of the wildfire would not be twisted into a hymn of triumph. The disaster would be reported with unsparing honesty. A month later, China Youth Daily published their three-part report on the wildfire in full pages with pictures — "Red Warnings," "Black Sighs," and "Green Sorrows." Each part was printed separately over several days, and the papers sold out each day.

The Black Dragon Fire in May, 1987. (Photo: Beijing News website)

The Black Dragon Fire in May, 1987. (Photo: Beijing News website)

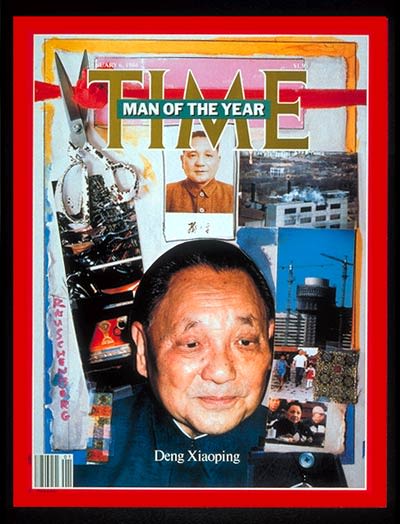

With reports such as these, frontline journalists were lobbing grenades over the battlements of the ivory tower, blasting loud and clear over the heads of universities’ journalism departments. The year before the Black Dragon Fire, Deng Xiaoping was on the cover of Time magazine and Cui Jian belted out “Nothing to My Name” during a landmark concert in Beijing. The zeitgeist of the eighties swept through everyone’s mind. Each media debate about journalistic practices became a hot topic in universities’ journalism departments. From the 1979 Bohai Oil Rig disaster to the 1988 National People’s Congress when Deputy Representative Huang Shunxing issued the first ever dissenting opinion, journalism students and scholars continuously debated, explored, and reflected on political reforms, social changes, the fate of the nations, and other major concerns.

Deng Xiaoping was on the cover of the Times magazine in 1986.

Deng Xiaoping was on the cover of the Times magazine in 1986.

These young journalists-in-the-making considered that reporters in the late 20th century were quasi-intellectuals and chose journalism as their career in order to promote national reforms.

Such a mindset prevailed in the journalism departments of universities. Print media was the absolute mainstream media platform. Landing a spot in a nationwide Chinese Communist Party newspaper was the dream of every journalism major. Very few journalism students ever considered other career paths. It was universally acknowledged that a journalism major graduate should find a job in the media after four years of college. Writing well for a respected media outlet was the ultimate realization one’s personal beliefs.

Fudan University Journalism Class of '86 alumnus Hong Bing remembered, "'Social responsibility' best sums up our ideals back then." For thirty years after his graduation, he stayed and taught in Fudan University, while Qiu Bing, Qin Shuo, and many other journalists from Fudan and other universities joined the press corps. Over time, they became the mainstays of China's media.

The 1990s: Supervision Through Public Opinions

When "Focus Report" (Jiaodian Fangtan) premiered on China Central Television (CCTV), it became an overnight sensation. Two years later, CCTV aired the "News Probe" (Xinwen Diaocha), a documentary program. The chief producer of the program was Qian Gang, who won the National Excellence in Investigative Reportage Award with his work of "The 1976 Tangshan Earthquake." At that time, journalists believed that the work of Party media outlets should adhere to the "correct direction of public opinions." This included not only the positive promotion of communism, but also supervision through public opinions to improve social governance. Be it in the field or in the academia, "Bear Justice with Iron Shoulders; Write News Articles with Sharp Pens" became journalists' motto.

In 1998, veteran reporter and editor Hu Shuli founded Caijing magazine, infusing what she learned in the United States to the industry. Meanwhile, Zhan Jiang, a journalism professor who directed a project translating the Pulitzer Prize Collection into Chinese, detailed the ideals of American journalism in the foreword of the translation. At this point, China had approved and elevated journalism to a tier-one discipline in higher education institutions. The concept of professionalism thus ensued, and the impacts over the next two decades were profound.

Meanwhile, the reform of market-oriented media progressed, and many local newspapers or evening editions such as Southern Metropolis Daily and China Business Daily gradually emerged. Both Party media and market-oriented media were very active. Writer and journalist Qian Gang left CCTV's News Report to serve as the deputy editor of the Guangzhou-based newspaper Southern Weekend. The reporters were active, and the outlook of journalism was promising.

Also that year, You Gang applied for the university in his hometown. The journalism department had just separated from the School of Chinese Studies and become an independent discipline. You Gang became one of the first journalism majors in his university. He witnessed the wave of expansion of college admission nation-wide as well as the exponential growth of students admitted to the departments of journalism.

You Gang remembered that at the new student orientation, there were seven professors present. The expectations from the faculty members were very clear: the students shall become reporters. What is a reporter? A reporter is an intellectual with a conscience and a spokesperson for vulnerable people, young You Gang believed. During his freshman year, You Gang looked for internship opportunities in media outlets everywhere. In his sophomore year, he went "solo." He would ride his bicycle around town to look for newsworthy topics and conduct interviews and later go home and work on his stories long into the night. He then would go to the offices of newspapers early in the morning to carefully place his news articles into the "submission boxes."

Allen (alias), who is one year older than You Gang, was admitted into the graduate program of the Beijing Broadcasting Institute (BBI), today's Communication University of China. In the second round of the admission exams, the subject was Jiang Zemin’s "The Important Thought of Three Represents" and "Ideals of Journalism." BBI has long been the source of talents for CCTV and China Broadcasting Network (CBN). Once a student is admitted to BBI, the student is guaranteed a bright future ahead. As a result, the Institute is highly competitive. There has been a case in which an individual from a local-level radio station was finally admitted after taking the annual admission exams five times.

Communication University of China, the former Beijing Broadcasting Institute (BBI). (Online photo)

Communication University of China, the former Beijing Broadcasting Institute (BBI). (Online photo)

There were not many hands-on courses in the graduate journalism program. What Allen can recall today were basic ideas such as the "inverted pyramids" and the "Xinhua style" of writing. However, the atmosphere on college campuses was fairly liberal. There were many lectures and forums. Allen often went on a one- to two-hour bus rides to Renmin University of China and Peking University to attend commentaries and presentations. There was a print shop near the west gate of the Peking University that could photocopy an entire library book in two weeks. He would bring 10 books at a time to make copies, including literature from the United States and from Taiwan.

Peking University (Online photo)

Peking University (Online photo)

According to Allen, in 2003, BBI hosted an "Investigative Reporting Workshop," attracting journalists from all over China to Beijing. He met Wang Keqin, first winner of the Correspondent of the Year in China, and Zheng Fei, who later rose to stardom.

This workshop became an important moment for the "golden years of investigative reporting." It was the same year that "Weekly Quality Report" (Meizhou Zhiliang Baogao), an investigative reporting program dedicated to product quality and food safety, was founded. 2003 was also when Southern Weekend published "The Death of Detainee Sun Zhigang," an explosive story about the migrant worker who died of physical abuse while being detained under China's custody and repatriation (C&R) system. 2003 was also the year that Beijing News and Oriental Morning Post were founded. Then, the outbreak of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, commonly known as SARS, made investigative reporter Chai Jin a household name in China. The image of the petit reporter dunning full personal protective equipment (PPE) and walking into the SARS ward in the hospital was etched in the memory of people in China. At the end of that year, CCTV rolled out the "2003 Best Reporter of the Year" award. Journalism became a highly respected and popular profession, attracting classes after classes of students to major in journalism, hoping that one day they could, too, become a "renowned journalist."

During this time, the transformation of commercial media also quietly began. Allen shared that journalism students had to face this reality upon graduation. Not everyone could make it into CCTV, and for those who did not make it, they mostly chose Party media outlets or ministry propaganda offices — "those jobs that could grant them a Beijing resident permit." No matter how respected Beijing News is, if commercial media cannot offer a resident permit, then those graduates would be better off with Sina, the online media company that could help them secure the much-desired Beijing resident permits.

Allen was hired by the business section of a Party newspaper. His job was to write critiques of businesses. However, he refused to call his writings investigative reports. "Back in those days, the definition of investigative reporting was very strict. It was to conduct investigations on public issues and concerns of the society. Imagine how much resistance we would face. We cannot call the research into a small business an investigative report…"

Photo:AP Photo / Greg Baker

Photo:AP Photo / Greg Baker

The 2000s: Professionalism

2003 marked the 15th year since the department of journalism in Fudan University had become the School of Journalism. It was also the year when Lin Fei was admitted to Fudan University. "Marxist journalism" was already firmly instilled in the program. Back in 2001, the Shanghai Municipal Committee Propaganda Department and Fudan announced a "co-establishment system" in the school of journalism. This joint program between state propaganda department and journalism school is often referred to as the "Fudan model," and the model was copied to universities nation-wide.

Fudan University (Online photo)

Fudan University (Online photo)

The professor who taught "interview writing" was an old school reporter. He used articles from Liberation Army Daily and Wen Wei Po. Lin could not remember what skills his professor had taught him in the "documentary" course, but he does remember, even today, the camera zooming in on the wailing victim, slowly, closer and closer — a negative example that the professor used to reiterate that "we journalists from the school of journalism shall never do such a thing."

Lin Fei covered entertainment news while working as an intern, and the deputy editor offered him a job. However, he did not accept the offer. The young man who often skipped classes to play games realized that when it came to his job, he wanted to do something that goes more in depth.

After graduation, he was hired by the Southern Weekend. He was more driven and motivated than he was at school. His colleagues had all had made their way publishing great stories they wrote. A colleague’s new great story in print was the most exciting things in the office. "We were really focused. All we talked about every day was news coverage."

Those were the glory days of the Southern Weekend. Qiao Zhong was admitted to a legal journalism major of a political science and law college in 2008. His undergraduate major was law. Initially, he did not care much about news. However, one of his roommates would buy a copy of Southern Weekend every week, and gradually the newspaper became a popular reading material in the dorm.

Southern Weekend's 1999 New Year Greeting said, "To empower the powerless, to push the pessimists forward." Qiao Zhong had heard about this greeting twice — first in his senior year language class in high school and again in a general education class in college. "Thinking back, it was just to inspire those poor intellectuals," he laughed. But at that time, Southern Weekend meant "the kind of news that we cannot yet produce, but that inspired us to become reporters like those in Southern Weekend."

Lin was determined to be a reporter. He did a few internships and realized that what he had learned in classes was useless. His mentor, a reporter, told him to "forget what you learned in school." So he started writing articles, and through his mentor's editing, he realized "this is how news articles should be written."

Now Qiao Zhong considered the school of journalism a guide that lead him towards journalism as a profession even though he had trained to become a lawyer. His unique major was the result of college admission expansion and of the increase of journalism schools. Qiao's major was designed to train and provide more propaganda talents for the Chinese judiciary system. Qiao Zhong was a product of his environment, but he ended up being one of the few who still remain in the media.

In comparison, Bai Kuan, who grew up in Guangzhou, experienced a more liberal environment. Bai went to Sun Yat-Sen University to major in journalism in 2008. The department of journalism was only established five years ago. Most of the faculty members were young and accessible. Professors who focused on theoretical concepts came from Hong Kong or from abroad, and they were very capable of conducting academic research. Most of the hands-on journalism classes were taught by reporters. When they talked about their own investigative reporting, they sometimes got so excited that they would bang on the desk or toss the chalk. "They cared about the public, and they were aware that there were a lot of complex issues in our country… they made you feel that the professional ideals of journalism were so respectable."

Sun Yat-Sen University (Online photo)

Sun Yat-Sen University (Online photo)

In his four years of undergraduate studies, he had observed the "2007 Xiamen Anti-p-Xylene Protest" and the "Flash Mob Rally for the Cantonese Language" in Guangzhou. He had discussed "civil society" and the balance between "objectivity and neutrality" in news on one hand and the power and the market on the other. He also accompanied a renowned journalist as part of the "Journalists in Residence" program to investigate the "Dust Lung Village," where a majority of villagers had contracted pneumoconiosis from work. In his junior year, Hu Shuli left Caijing magazine and became the dean of the school of journalism in his university.

Bai Kuan stayed to continue his research after he earned his doctoral degree. He still cared about civic movements. He enjoyed all those years he spent in college. "Thinking back, I feel so grateful. That was where I shaped who I am today."

Journalism scholar Zhan Jiang summed up the first decade of the 21st century: "At that time, the political atmosphere in China was fairly relaxed. Professionalism led the way. Renowned scholars and journalists were respected and followed as models. In terms of journalism education, you could pretty much talk about anything as long as you did not oppose the 'Four Cardinal Principles' of upholding the socialist path, upholding the people's democratic dictatorship, upholding the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and upholding Mao Zedong Thought and Marxism–Leninism…There were a lot of idealists, especially in the top schools."

Not all universities in China can be top schools though. Different schools have different standards, quality of education, and educational resources. Journalists graduating from lower-tier, less endowed schools sometimes found their education confusing and at odds with their ideals. For example, Zhao Wenwen likes to watch Phoenix TV, and she idolized Luqiu Luwei, nicknamed the Battlefield Rose for being the first female reporter to cover the War in Afghanistan in 2001. There was a time when Zhao was very confused. On the one hand, the department chair often used good investigative reports for case studies and to teach them that "what a journalist writes may determine the fate of a person." On the other hand, after a professor asserted that the "Touching China" program was mostly "rigged," he then spoke about how to manipulate a program.

There were not many job opportunities in the city where Zhao Wenwen graduated in Hunan. She interned at a local Party newspaper and found the operation different from "what I had imagined about news." Her university made little effort to nurture the next generation reporters it was sending out into the world, caring instead about admissions into their post-graduate programs and the employment rate of the graduates. Zhao Wenwen was discouraged and did not want to be a journalist anymore, so she changed her career path and became a teacher. Today, the university she works in has been promoted to a first-tier university, while her alma mater has eliminated the broadcasting journalism program that Zhao Wenwen studied in.

The 2010s: Major Changes

The downfall of newspapers seemed to happen overnight. In 2013, the Guangdong Province Propaganda Department went well beyond traditional protocol to censor Southern Weekend's New Year Greetings. The paper was forced at the last minute to print the Propaganda Department’s revised New Year Greeting, which contained numerous errors that outraged the paper's readers. In response to numerous complaints, Southern Weekend's editors published an online statement criticizing the Propaganda Department director for violating the paper's editorial independence and forcing major last-minute changes to print content. This incident marks a moment in the modern history of Chinese journalism when government agencies decided to take more comprehensive control of Chinese media outlets in order to refashion them into propaganda platforms.

After the 2013 New Year's Greeting Incident, many journalists left Southern Weekend. In 2013, Lin Fei also left. By the end of that year, only one of his original colleagues remained.

The incident was just the beginning. What followed was a steady erosion in print media's ethical standards driven not just by increasing government censorship, but also by commercial media's profit-making and socioeconomic trends — all of which combined to make true investigative journalism harder to conduct.

Metropolitan newspapers seeking financial self-sufficiency turned to advertising as a source of revenue. As ad revenues became a greater and greater share in newspapers' total revenue, newspapers compromised their journalistic ethics and refused to allow reporters to conduct investigations into the newspapers' advertisers.

In commercial media, the title "reporter" does not bear the same glory of the profession and the recognition of the society anymore. The barrier for entry into journalism was lowered, and there have been cases where so-called reporters violated the code of journalism ethics to blackmail their subjects.

Journalists are also not compensated well because of skyrocketing costs of living and reduced opportunities for journalists to supplement their base salaries with bonuses and freelance reporting. In the first three years when Lin was on the job, he could make as much as 40,000 RMB a month. Back then, an apartment unit cost less than 10,000 RMB. Three to four years after he was on board, his income had dropped to between ten to twenty thousand RMB, but by then the housing cost has doubled.

Those who stayed described themselves as "holding down the fort." Allen, who had switched gears to work in fashion media, mocked himself. He still had some idealistic ambitions about journalism, but when he saw those more experienced and better-known reporters forsake journalism, "do you think you can do it? The times have changed. It will be very difficult to survive if you are too idealistic."

Many blog platforms appeared in 2011. (Photo: Reuters / Stringer)

Many blog platforms appeared in 2011. (Photo: Reuters / Stringer)

When Lin Fei left Southern Weekend, there were more than 500 million registered users in Sina's Weibo, the Chinese equivalence of Twitter. Shortly after, WeChat rolled out "Public Account," a feature that enables registered users to push feeds to subscribers, to interact with subscribers, and to provide services to subscribers. The era in which "everyone can be heard" had arrived. Newspapers were trying to find a strategy to react to the change. In 2014, Oriental Morning Post introduced "The Paper" (Pengpai), a new media project that provided the media outlet's articles online to its readers. Three years later, the entire newspaper switched to digital format. Those newspapers that did not react timely ended up closing for business.

When "The Paper" was rolled out online, the CEO of Oriental Morning Post Qiu Bing issued an inaugural statement, "My heart is pounding steadfastly just like yesterday," to remember the 1980s that he had cherished. Wu Wen, a journalism student in a second-tier university, read the statement and felt "the lights of idealism shine on a young man of a small town." "Focusing on the individuals" was what had moved him. Now that he has become a reporter, he reflects that the exploration on the complexity of human nature is the most intriguing characteristics of journalism.

Wu Wen recalled in his college days that the core courses focused mainly on indoctrination. The professors did not talk about ideals much. Attending classes was just a necessity.

Wu Wen interned at "The Paper" for three months in 2015 and felt he learned more during his three-month internship than during all four years of college. Although he constantly skipped classes, the local bureau of a state media outlet hired him after graduation due to his internship experiences. Unlike Wu Wen, who graduated from a second-tier university, most of his coworkers were graduates of top-tier universities.

That same year, Yang Fang was hired in the headquarters of a state media outlet after earning his graduate degree from Peking University's School of Journalism and Communication. In Yang's view, formal education in journalism is not important. Critical thinking is the essence of the discipline. His graduate studies were not a hands-on experience at all. They focused instead on reading of theories and literature reviews, but they were eye-opening. He had a crash course in the humanities and culture and essential elements of good reporting during his years in graduate studies.

Yet only a quarter of his classmates worked in journalism after graduation. After the reform of commercial media, there are different categories of reporters in state media — "business hired" and "station hired" — and reporters' salaries in the two categories varied significantly. For those who graduated from top universities in Beijing, they could have a better career outcome if they seek a job in a state-run business or a position in the public sector.

On the other hand, in 2015 there were already more than 600 universities in China offering journalism or another media-related major with about 230,000 students in those majors. The supply of journalists far exceeds the demand. On the one hand, the business of traditional newspaper media is declining, while on the other hand, the number of journalism graduates is growing exponentially.

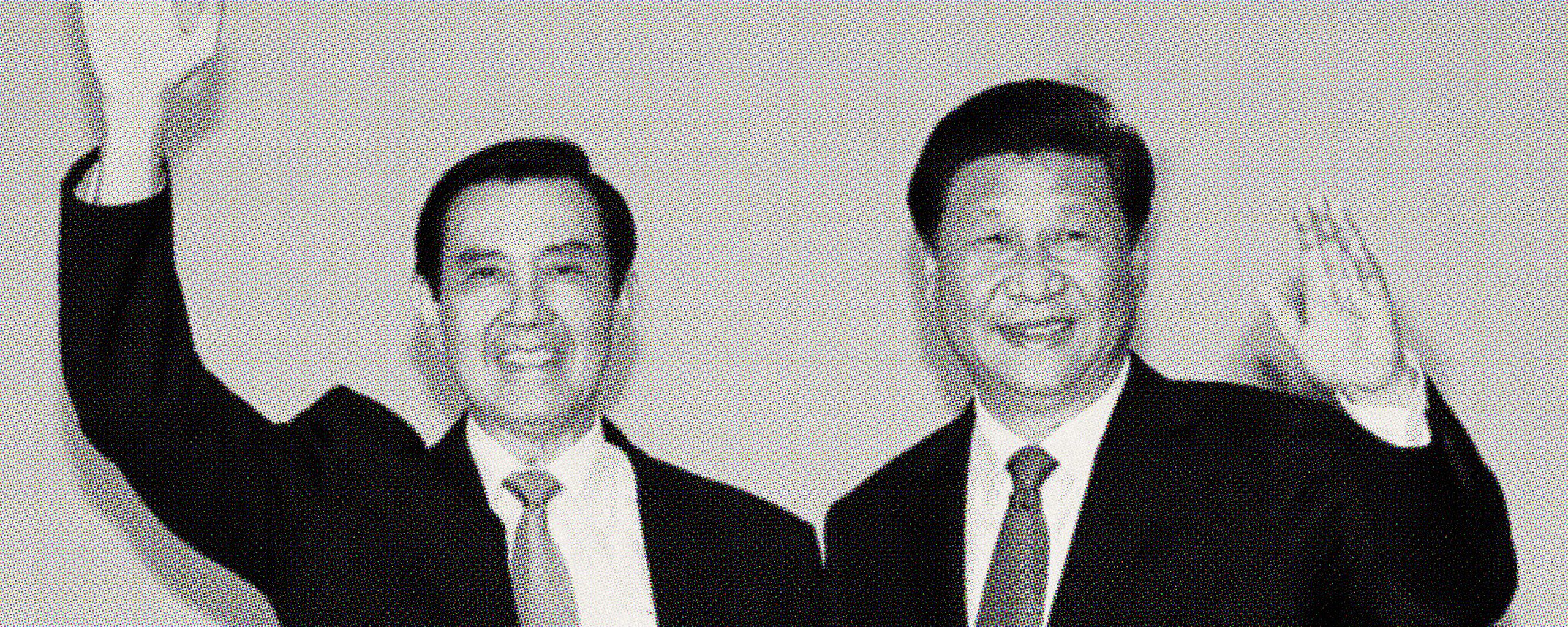

To Yang Fang, working in the media means working for Party media outlets. The mission of a reporter is to record an event. If the reporter cannot record the event, he/she should at least witness it. However, one can only gain access to major historical events in a large media outlet. "Take the meeting between Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-Jeou, for example. If I could have covered that meeting, that would have been the highlight of my career and I could retell the story over and over."

The meeting between Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-Jeou in Singapore in 2015. (Photo: Taiwan Presidential Office)

The meeting between Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-Jeou in Singapore in 2015. (Photo: Taiwan Presidential Office)

Bai Kuan shared the sentiment. He left China in 2013 to study abroad for his doctorate. He could already feel the changes in atmosphere in China. The ideological control in colleges was tightening, and many professors either resigned on their own or were forced to leave their posts because of their comments. Bai Kuan teaches at a university now, and he feels that the students today are very different from that of his generation. "They seem to desire mainstream media only. They want to land a job in major media outlets, major Party newspapers, or major television stations. In my day, we would have chosen media outlets like the Nanfang Media Group, Caixin, or Sanlian."

Yang Fang does not dismiss these media outlets or consider their investigative reports unimportant. He even prefers Pulitzer Prize style reporting. "But we can report our news that way. We have our own Chinese characteristics." To conduct investigative reports, there should be a good environment for public opinions. "In the current [environment], what can you investigate?" When he first started working, he wanted to write about everything, but he could not write in the style that he liked. Gradually, he compromised: "We are young. We should learn first. We should not be too sharp and outspoken."

After his graduation, Yang Fang still went back to Peking University from time to time to attend Commentator of China Youth Daily Cao Lin's talks. Yang Fang particularly likes how Cao navigates his commentaries within the allowed limits. "He knows exactly where to draw that line. He says enough for the audience to enjoy, but then he is still within the party line and will not be censored."

Yang has left the Party media outlet and found a job in a business. He has considered returning to media and focusing on financial news, because "business reporters make the most money."

The Young Generation

Meanwhile, there are still others who do not care about money.

Xiao Tang, a 2018 journalism graduate, was driven by his interest in this profession. Around the time when he was to claim his major, he read the SARS reporter Chai Jing's autobiography "Insight." He chose journalism because he was inspired by her book. In his recollection, most of his teachers talked about the objectivity of journalism — balancing the sources, reporting both sides of a story, exercising self-restraint in interviews and writing, and trying to present the truth as much as possible.

The cover of Chai Jing's Insight. (Online photo)

The cover of Chai Jing's Insight. (Online photo)

He particularly enjoyed journalism scholar Hong Bing's course "Reporting on Public Affairs." The students would read news articles, and the assignments required the students to exchange communications with the reporter who wrote the piece that they read. He has learned a lot from the process. In his view, Hong Bing is a professor with deep feelings for the profession.

"Every day, Professor Hong encouraged us to become a reporter," Xiao Tang said. And he did. However, he found what he was lacking once he set foot in the real world: the lack of academic perspective caused an inability to establish a proper reporting framework, such as the code of interview ethics, difficulties he faced on the job, and gaps between theory and practice.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. As the conventional news media faces a decline, the newly emerging media is rapidly on the rise. It is getting harder and harder to "write with your sharp pen around the world." Short video clips, the use of Photoshop, WeChat public accounts, how to gain 10,000 likes all abound. Today's media outlets demand journalists to work across multimedia platforms, but the training in the journalism programs of institutions of higher learning lag behind.

Xiao Tang does not see being a reporter as his lifelong career. How long he will stay depends on whether he can produce something to his satisfaction, on his relationship with his editor, and on whether he can resolve his aesthetic differences with his supervisor. Tightening censorship on reporting in recent years is trying his patience.

A journalism professor who asked to remain anonymous pointed out that, "a decade ago, many reporters were young graduates from small towns, but nowadays most of the journalism students in top universities are from middle class families in metropolitan areas. They value self-realization more, and they prefer to 'live in the moment.' They do not care so much about the grand mission bestowed upon the media."

Hong Bing considers their "shying away from media heroism" a good thing that is reasonable and progressive. However, it has been years since he last actively encouraged his students to seek a career in journalism. Up until five or six years ago, he still sincerely considered a job in journalism to be great training for one’s abilities. It would not hurt to work in the field for a few years. Now he is taking a more cautious approach. If a student comes to him for advice, he first inquires whether the student is certain that they are still interested in the profession after their internship, whether they feel that they have achieved some degree of professional satisfaction, having written a reporting article that they would enjoy rereading in a few years. Then Hong Bing makes sure whether the student faces expectations and pressure from their family to buy a house in major city such as Beijing, Shanghai, or Guangdong. Only when he is satisfied with the student's answers will he recommend the student to give the discipline a try.

Students benefit from studying journalism regardless of whether they actually become journalists. At least to Xiao Tang, he felt he was better educated in media literacy, from the verification of information, selecting the news sources, and awareness of the need to fact-check when reading the news. In an era where real and fake news flood the internet, his training helps keep him calm and sane.

Chen Chen, a journalism student in a foreign language college, prefers to "jailbreak out of the Great Firewall to see the world." The international journalism program she attends was established in the 1980s, aiming to train journalists for global propaganda. Chen Chen considers it funny to keep this program in today’s environment. Not many who graduated before her have become journalists.

Nevertheless, a joint memorandum issued by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Propaganda in 2018 stated that universities were to "establish educational bases for Marxist journalism research and propaganda" to nurture "excellent young journalism and broadcasting talents who can do a good job in telling China’s story and broadcasting the voice of China." The training of international journalism and communication talents was listed as a key objective.

Chen Chen's interest in "global propaganda" only emerged after she completed her internship, because she felt that the current foreign language Party media outlets "are writing fake news, taking [foreign language news] out of context, and carrying out the government's agenda." She feels that it would be meaningful for her to get a job in a state media outlet so she can make some changes in her own way, even if it is just a little.

In Chen Chen's view, the media should serve in the interests of the public. She has interned at a website where her job was to copy tabloid news. The amount of such news was tremendous, but it also made her uncomfortable. She almost never followed Xinhua or People's Daily. "Other than those journalism majors like us, where do you find young people who would read news from those sources?" The self-media is grabbing a lot more views, and some of them do offer better quality reporting.

The training Chen received in the foreign language college also allows her to read news from foreign media outlets, which in turn gives her a clearer perspective. Media in China is bound by political censorship, whereas media outlets in other countries are influenced by businesses. There are the ones leaning left, while some others lean right. There is no such a thing as absolute "objectivity and neutrality." She listened to the lectures in the classroom, but she may not take everything said at its face value.

As educators see it, this generation of students grew up in the world of the internet. They are fast learners born with abilities to consolidate information and manipulate digital technology. They start worrying about job opportunities as freshmen. They know what they want, and they know how to reach their career goals for jobs in desirable news platforms through active learning and using their talents.

Today, You Gang is a professor in a school of journalism and communication. He plays the video clip of the "2003 Best Reporter of the Year" and shares the Pulitzer Prize collection with his students. He told his students that for journalists, reporting news in the interests of the public is just the beginning. The caring for human beings is where the true value of journalism lies. However, he is also aware that today's journalism schools not only train reporters, but also train them in all the other communications-related talents, where market demand is.

He predicts that "society needs professional journalists to report the news. There will be fewer top journalists, but their values will be much stronger. On the other hand, if every citizen in China increases his or her media literacy, then it will be much easier to promote public communication."

Hong Bing recalled an incident that happened a few months ago. A WeChat public account named "Qingnian Dayuan" published an article titled, "Were It Not for the Australian Wildfire, I Wouldn't Have Known China Was This Awesome 33 Years Ago." The post compared how Australia handled the wildfire to China's efforts in putting out the Black Dragon Fire of 1987. The post instantly went viral and received more than 100,000 likes, but it also caused hot debates on the internet and drew criticism from commentators about its cheap trick of using patriotism to generate page views in the face of a natural disaster. Two different generations of youth, more than three decades apart, have written extremely different footnotes to the term, "news."

(The names of the interviewees have been replaced with pseudonyms.)

The aftermath of the 1987 Black Dragon Fire. (Photo: Beijing News website)

The aftermath of the 1987 Black Dragon Fire. (Photo: Beijing News website)

Backgroup photos: AP (Neal Ulevich, Bullit Marquez), AFP, Reuters (Thomas Peter, Carlos Barria)