Whither non-fiction?

How Chinese non-fiction writing moved away from public discourse

I was thinking about Li Zixin recently, who founded and launched SandwiChina: A Storytelling Academy, and the program that he called China's "first non-fiction writing incubation channel" with a great sense of loss.

By September 2015, China was seeing the peak of a wave of new online businesses across most sectors and industries in China. Non-fiction -- a concept that was once an import in China -- has now been repackaged as content by online entrepreneurs. An influx of capital has breathed new life into this long-forgotten writing form, and major media outlets have been lining up to start non-fiction writing channels.

SandwiChina launched its non-fiction incubator as "probably the most impressive writing tutorial group in history." It included a number of notable figures from contemporary popular non-fiction platforms, including: Guan Jun from NetEase's Renjian platform; Guo Yujie and Xie Ding, creators of Interface's NoonStory; Wei Chuanju, who implemented Tencent's Guyu project; Lin Shanshan and Du Qiang, the main writers for Esquire's China edition; Zhang Zhuo, deputy editor of Renwu; and He Tao, editor-in-chief of the Chinese edition of GQ. It offered guidance and mentoring to writers as well as contacts in online publishing. Its aim was to enable writers to write detailed, realistic pieces about contemporary China.

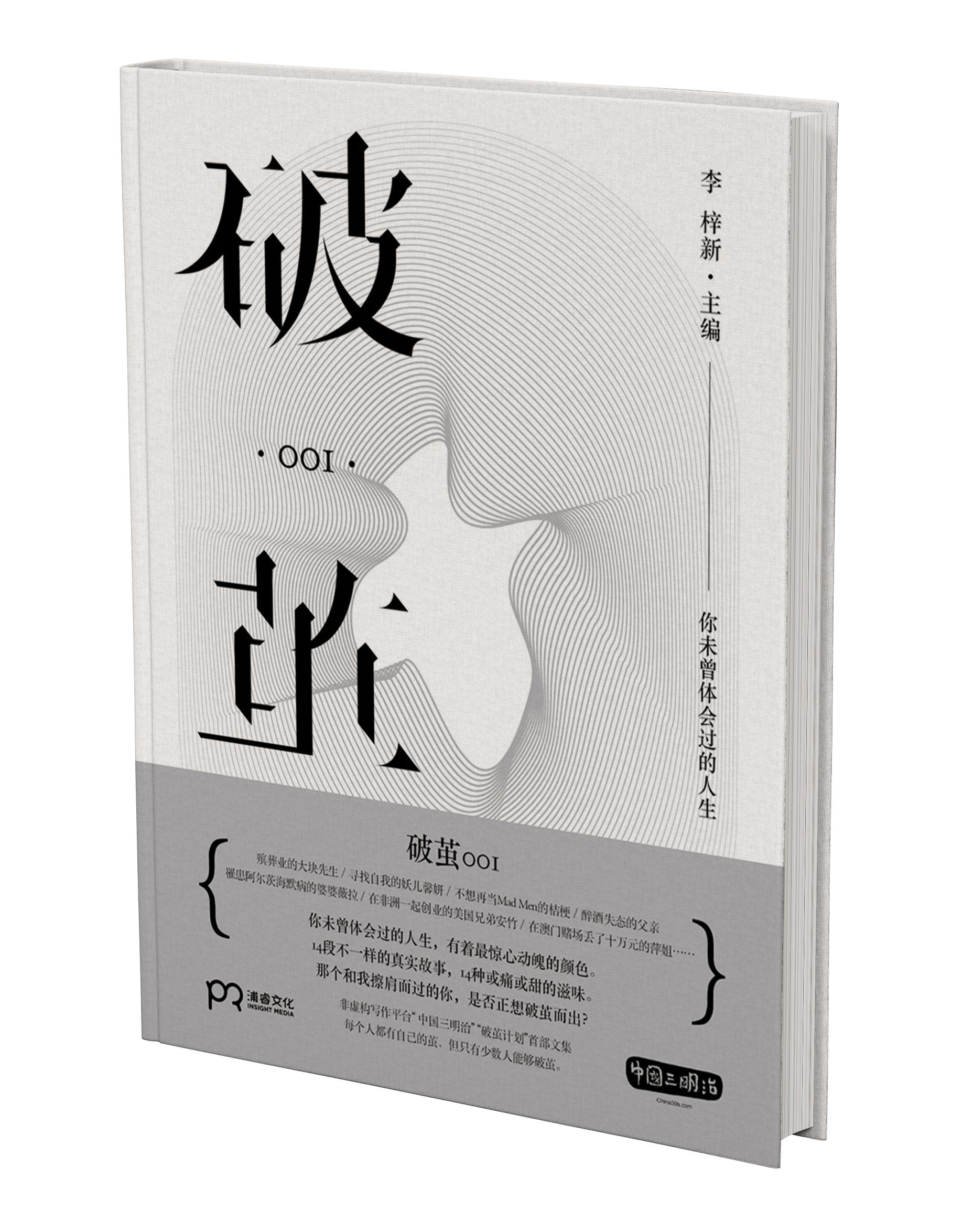

SandwiChina's first story collection from its non-fiction incubator (Online photo)

SandwiChina's first story collection from its non-fiction incubator (Online photo)

Five years on, these platforms are almost unrecognizable. NoonStory was disbanded at the end of March 2020 after colleagues reported He Tao for "fabricating facts" and sexual harassment. He resigned; Lin Shanshan and Du Qiang got to enjoy a further six months at their ONE lab, before everyone moved to a new, independent writing studio called Hardcore Stories, which wasn't often updated. Guyu and Renwu are still there, but repackaged for the urban middle classes, and a lot of stuff on there, according to Li Zixin, is "so dull."

"It feels a bit post-apocalyptic," Li sighs. But he is reluctant to talk about the reasons behind these changes. Political pressure from officials and from investors is an all-too-common topic these days. Like many people who set up non-fiction platforms, he is forced to accept this new reality, and to tentatively seek out new spaces and acceptable topics in an increasingly tense political atmosphere.

Not making money is the biggest sin of all.

On March 31, Ye San, one of NoonStory's rotating team of editors, posted the following on Weibo: "The NoonStory team has been disbanded. Operation of all social media accounts has been transferred to Interface. So this is goodbye. Thank you to all of our colleagues, friends and supporters. I hope we meet again."

Ten days later, NoonStory's founder and editor-in-chief Guo Yujie revealed further details about the shutting down of the site on Weibo. She wrote: "On March 3, we received news from Interface management that NoonStory was shut down because it wasn't a part of the company's core business, and had been negatively affected by the economic downturn owing to the coronavirus pandemic." Twelve days later, the last manuscript was published, all the staff left, and the team was officially disbanded after being in business for five years. But its disappearance stirred huge public interest, and started a debate about the state of non-fiction writing in China.

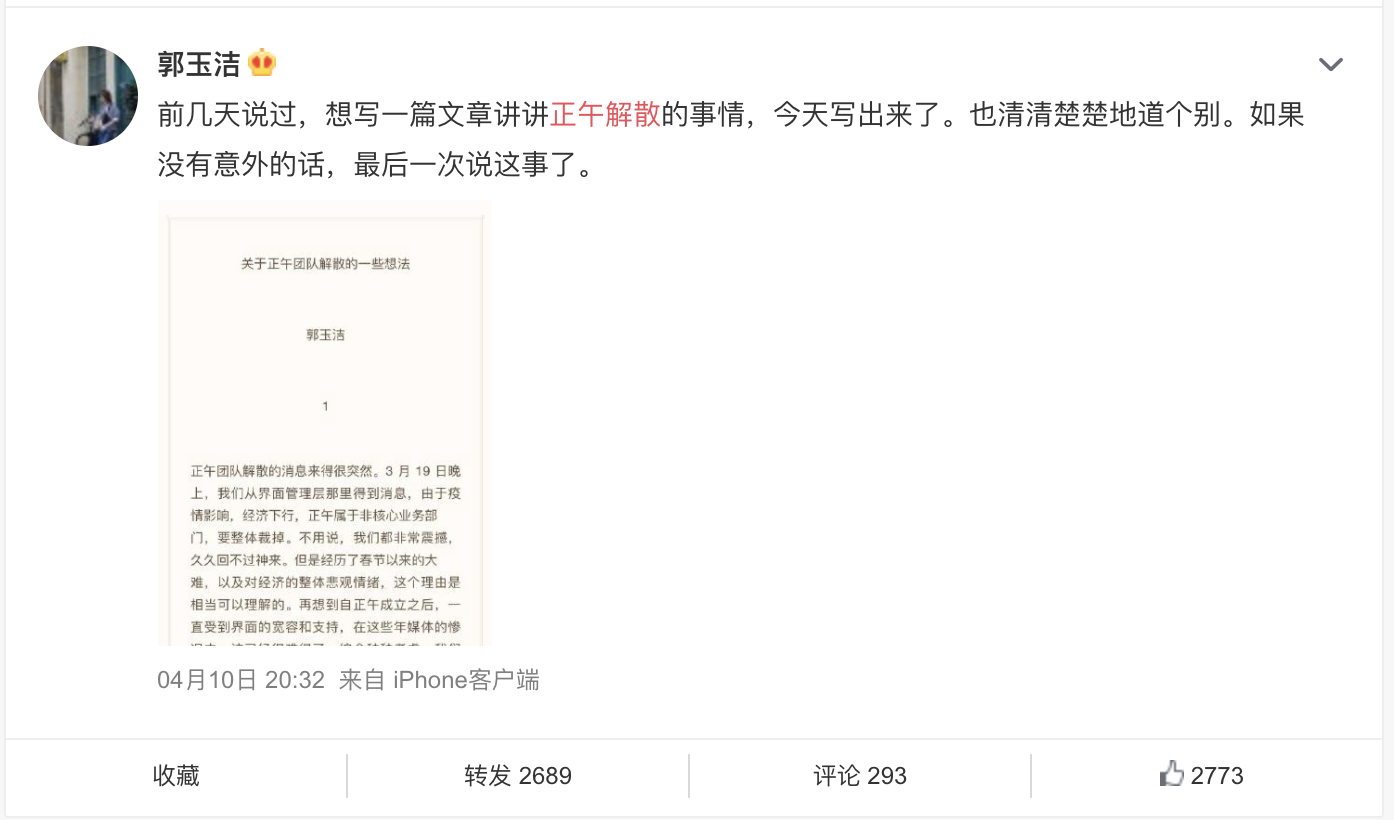

Screenshot of Guo Yujie's Weibo Post (From Weibo)

Screenshot of Guo Yujie's Weibo Post (From Weibo)

Guo Yujie joined Interface in August 2014 as head of the features department. By the following April, that department was renamed NoonStory, sparking a new craze for contemporary non-fiction writing. NoonStory had relatively few followers compared with other, more news driven platforms. But it also had a number of bestsellers, despite not sticking to the hot topic of the day.

"[Our stuff] showed a deep understanding of people, particularly ordinary people, which I think really spoke to a lot of readers," Guo says. As she wrote in the preface of the first issue of NoonStory, titled "I climb over the wall," "The main story in China today is the story of Ma Yun and the thousands of people like him. We need to learn story-telling to avoid uniformity; to subject reality to our gaze, to let forgotten things live again, and to enhance the dignity of ordinary life, for a richer, more imaginative China."

But such words lose their vitality when faced with the harsh realities of capitalism. "NoonStory's biggest failing was that it didn't make money," Guo says, adding that when the management announced it was shutting the operation down, she felt as if all of their efforts had dissolved into nothing in the face of the requirements of capitalism.

Guo Yujie, NoonStory founder (Photo: The Paper)

Guo Yujie, NoonStory founder (Photo: The Paper)

Actually, something similar had already occurred back in October 2017. The non-fiction writing team ONE Lab, which formed a part of a cultural brand started by former race driver Han Han, and headed by prominent feature-writer Li Haipeng also folded. The team included other high-quality writers including Lin Shanshan who wrote "Child Matricide" and Du Qiang who followed Li Haipeng from Esquire, who sold the film and television rights to his "Pacific Battle Royale" to LeTV Pictures for a cool 30 million yuan, as well as Wei Ling, ("Made in Dongguan"), Qian Yang ("Smog Over Beijing"), and Wang Tianting ("Beijing After Midnight"). In the industry, they were known as the dream team.

But the glory days were not to last. ONE Lab officially launched on January 1. By July 5, it had published its last new story. The last post was an announcement that team member Du Qiang's new work "Life and Death in the Badain Jaran Desert" would also be made into a movie: the first and last work to come out of the project that would successfully sell film and TV rights. In just six months, the team produced around 10 original works of non-fiction.

Massacre of The Pacific, a non-fiction story earned over 30 million views. (Online photo)

Massacre of The Pacific, a non-fiction story earned over 30 million views. (Online photo)

Part of the reason was that there is a huge difference between effort and output when it comes to non-fiction writing. The lead time for special features is very long, research costs are high, and it is hard to make a profit. And a dream team needs to be paid a high salary.

Such are the factors affecting non-fiction when it tries to go commercial. Tencent editor-in-chief Li Fang and deputy editor-in-chief Yang Ruichun have both said publicly that non-fiction is a costly luxury. Lin Tianhong, a former colleague of Li Haipeng who also worked for Han Han's Tingdong Culture brand, once said: "Non-fiction can only boost its commercial value by getting into the world of TV." But this also means that the stories that don't make it into TV are rarer than hen's teeth.

Take the non-fiction platform Real Story Project, which was founded in 2016. It is still exploring the commercial possibilities of TV adaptations, and has garnered more than three million fans in a couple of years and published more than 300 stories, of which around 20-30 have been sold for TV or film. SandwiChina advocates a wider audience for non-fiction work, and runs non-fiction creative writing courses for amateurs. At the same time, it is trying to find profitable, small-scale channels for a number of new creative products. But Li Zixin isn't optimistic. SandwiChina reported heavy losses in 2019, and reduced its full-time staff to around six or seven people. And the future looks even more uncertain in the wake of the pandemic.

Han Han, founder of Ting Dong Culture (Online photo)

Han Han, founder of Ting Dong Culture (Online photo)

Public and private

no longer mix.

Most non-fiction channels survive because they form part of larger platforms. Guyu and Hardcore, reorganized by the original team of ONE Lab, are backed by Tencent News, while Renwu belongs to Netease's news division. Jidi Studio is one of Sohu News' original departments, and the special feature teams at GQ and Esquire have the backing of fashion magazines and their parent companies.

And such platforms are inevitably limited in their choice of topics, whether owing to online censorship or by the need to produce a certain volume of content. A reporter who once worked for a non-fiction platform said that after the channel was shut down by the authorities after it reported on an explosion that occurred in Xiangshui in 2019. But even when the channel was relaunched, it was subjected to a great deal more self-censorship by the team itself. Reporters could often be heard muttering "I don't even know if we can write about this stuff any more," while editors spent their days coming up with the safest possible way to approach things. As a sub-channel of Tencent News, the well-developed non-fiction platform Guyu was also sanctioned by China's Cyberspace Administration during the pandemic for "illegally acquiring and disseminating fake news," among other issues.

Under such heavy pressure, non-fiction platforms have adjusted their positioning, and changed the subjects they write about. Most platforms limit themselves to safer "middle-class", "urban" topics that offer "moving" stories to their readers and that boost traffic to the channel. This means that content is getting more and more homogenized, and readers are getting less and less interested in it.

SandwiChina has tried to stick to its original branding by offering a wider variety of individual stories. During the pandemic, the platform has drawn on a network of writers all over the world to publish stories from people who have had coronavirus, international students, and the ones who were unable to go back home in China, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, among other countries. The stories may be fragmented, but they actually offer different perspectives on life.

NoonStory now positions itself as a small workshop telling the stories of ordinary people. Guo Yujie wrote in the second issue of NoonStory, that diversity and creativity coming out of multiple small workshops could produce excellence.

Guo Yujie lead the non-fiction writing studio of "The Paper · Fudan" (Photo: The Paper)

Guo Yujie lead the non-fiction writing studio of "The Paper · Fudan" (Photo: The Paper)

But she also realizes that these stories need a broad appeal and a certain social relevance, something she regretted not doing when the platform folded. She cites a quotation from Confucius about texts needing both vernacular and aesthetic elements to be successful.

Li Zixin admits that a lot of non-fiction out there at the moment bores him to tears. When faced with a limited choice of topics and a requirement to keep producing, most people will choose topics that have immediate and broad appeal, interview one or two people as illustrative cases, and write up their stories. "As soon as I look at the title, I know what it's going to say, so I have no desire to click on it," Li says. But he adds quickly: "It's not that it's bad. Without it, there'd be nothing at all."

Li Zixin, founder of SandwiChina (online photo)

Li Zixin, founder of SandwiChina (online photo)

A space to explore

As media organizations explore new business models and editors find ways to operate in the gaps left by censors, non-fiction writers are also trying on new literary styles.

Du Qiang's trajectory, from Esquire to ONE Lab to Hardcore, is fairly typical of his peers in this industry in recent years, including political reporters and investigative journalists. He has been moving to a form of non-fiction that is more like fiction, in that it is literary in style. The huge pressures of censorship in news have led to a new transformation in the industry. In an interview with the Initium, Li Haipeng said: "In traditional media, the ship is sinking... only the mast is still standing." "A few crew members are still holding onto that mast...and they are doing non-fiction."

Du Qiang points out the difference between a feature article and non-fiction in an interview with Quan Media. "The starting point of the former is reporting, and that of the latter is literature," he is quoted as saying. He says personal expression is important in non-fiction works, and that he isn't shy about revealing his own feelings through his writing. "Don't cover things up; if you make judgments or feel something, then you have to make that clear," he says. "Trying to conceal your personal opinion in a faux-objective narrative is the worst thing you can do," he says.

Du Qiang (Photo: The Paper)

Du Qiang (Photo: The Paper)

Non-fiction is increasingly coming to grips with reporting based on personal experience, immersive writing and the use of the first person. Li Zixin says: "Chinese journalism doesn't provide writers with enough space to explore or enough credit for their work. So, people who like to write are naturally going to move in a more literary direction." Li says several factors are at work here. Firstly, it's hard to dig out facts and go into much depth in non-fiction writing in China, so a more literary text is the next best thing, Li says. And a lot of talented non-fiction writers also have literary ambitions, so they are willing to try their hand at more of this work.

"This also echoes a current tendency to pay more attention to the feelings of individuals," Li says. He thinks it's hard to be totally objective as a writer, because everyone draws on a unique experience and set of emotions. Du Qiang says something similar in his interview with Quan Media. "There is no God's-eye-view in non-fiction writing produced by human beings," he is quoted as saying. He says that most non-fiction writers are able to recognize these limitations, and are able to keep their sources of information transparent while at the same time revealing their own feelings about the topic at hand.

"There is no absolute objectivity, only absolute limitation," Du says. Du Qiang believes that objectivity is rather a style adopted by writers, and one that should be made to undergo rigorous fact-checking to ensure accuracy. Hardcore is currently the only non-fiction platform in China to hire a fact-checker, although ONE Lab did so while it was running. Every fact in every article is verified with recordings or written references.

The tendency towards more literary storytelling makes it hard for newcomers to the industry to develop, however. In 2019, the head of the long-shuttered investigative supplement Freezing Point said on the Guyu non-fiction writers' forum that a lot of writers nowadays tend to pay more attention to their technique than to the power of a good story. They lack respect for stories, he wrote, adding: "You are all in too much of a hurry, because you are so young." Renwu editor Zhang Han thinks millennial journalists lack a clearly defined point of view.

Li Zixin has noticed the same problem. He thinks that the overall culture, where utilitarianism and individualism dominate, is to blame. An increasing emphasis on entertainment and celebrity culture has also affected young people's sensibility, their capacity for independent thought, and their social awareness. For Li, this problem is as intractable as the commercial difficulties and strict censorship faced by the industry. The best he can hope for is to discover some fresh writing talent from among the amateur population, to encourage more people to write non-fiction, and to keep the flame alive for the future.

Background photos: Reuters, online photos