The Truth Isn't Dead:

You Just Don’t Believe It Anymore

What is the most effective way for a dictator to deal with an influential dissident?

Do away with him or her? No. A sudden disappearance would only boost their influence. The collective mourning sparked by such deaths often marks the transformation of speech into political action. From the point of view of the dictator, the dissident is less important than those who follow him or her. What matters most is regaining control of their hearts and minds.

So how does a dictator go about weakening and eliminating the influence of dissidents on the masses? Through isolation, by smearing their names, and by offering a competing point of view. The trick isn't to annihilate a dissident, but instead to limit his or her ability exert influence and to speak in their own defence. For every dissident, there needs to be 10 people with orders to distract his supporters and compete for their attention. They need to find his weaknesses, his Achilles heel, and use them to discredit him and destroy public trust in him. At this point, the dissident is still around, and can even speak out, but people can no longer hear him or her, or even if they can, no-one believes them anymore. They are no longer a threat.

This process is very familiar to any observer of totalitarian governments. Maybe you can even remember some of the names of dissidents who were in the public eye for many years. But where are they now? What has become of these anti-totalitarian activists today?

The biggest threat to any totalitarian regime doesn't lie with any individual, but with the truth itself. The process just described isn't just a way to deal with dissidents. It is also a way for totalitarian governments to suppress the truth.

But the truth is everywhere. It doesn't reside in a single person or piece of writing that can be easily isolated or discredited. So in the past, dealing with the truth wasn't as simple as just dealing with a few dissidents.

The most common method of controlling public opinion is a traditional one, based on blocking the spread of accurate information: it involves shutting down social media accounts and deleting posts. But this type of operation, while it does silence people on a huge scale, will also mean that the information attracts even more attention in certain circles, and spreads more quickly because of the ban. Totalitarian governments are fortunate to have information technology these days; the power of algorithms based on large amounts of data. They have a far greater capacity to control public expression, to fine-tune those controls and to suppress the truth with ever-greater precision.

So what does this refined method of information control and censorship look like? How does it gradually take hold?

Three things I have encountered in the realm of Chinese public opinion control and monitoring spring to mind that illustrate the slow and careful changes I am talking about.

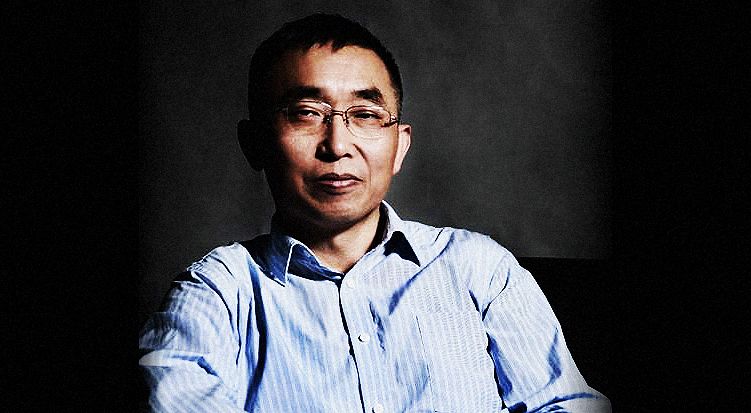

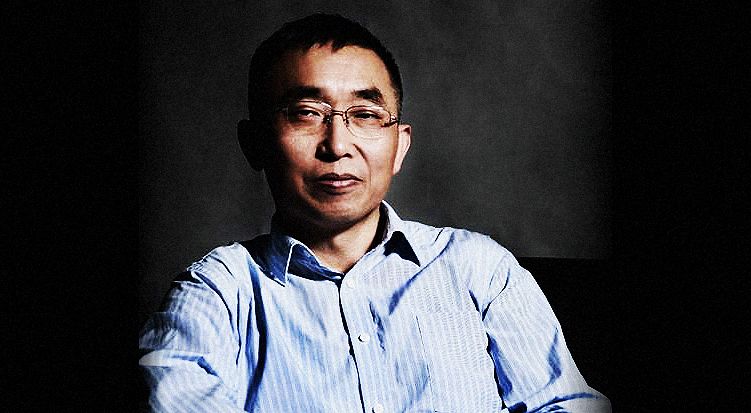

The first emerged in the Chinese media industry around 2008. It was the Public Opinion Monitoring Office [later renamed the Public Opinion Data Center]. This agency had its roots in a magazine set up by the People's Daily titled "Policy Information," which was later renamed "Online Public Opinion." The tagline on the cover clearly stated its mission: "Helping senior officials to read the internet." Its editor-in-chief Zhu Huaxin was a communications scholar with in-depth experience in official media. He went on to become the deputy director of the Public Opinion Monitoring Office.

Zhu Huaxin, deputy director of Public Opinion Monitoring Office (Online Photo)

Zhu Huaxin, deputy director of Public Opinion Monitoring Office (Online Photo)

Back then, there were 250 million Chinese internet users; the largest number in the world. But there was also the emergence of Web 2.0 and social media, democratizing the online experience and giving everyone a voice. There was an explosion of online information, hot topics were being amplified, and mass incidents could happen and public opinions form about them in a very short space of time. For civil society, it was seen as a great opportunity to increase online presence and set the public opinion agenda around important events. China would be changed if everyone was watching, and the government would be forced to yield to the weight of public opinion.

But the government soon realized that the official voice was quickly losing its influence in social networks. No one wanted to read anything officially written. The government became the target of mockery, while market-oriented media organized already practiced at speaking to people in their own language and witty public intellectuals were the new rock stars of public opinion.

The government could see that this was a crisis, and so it decided that it would need to intervene to change the direction of online expression. And so the Public Opinion Monitoring Office dedicated to "helping senior officials read the internet" became an official think tank providing crucial analysis of public opinion and engineering solutions for government agencies at all levels.

Interestingly, their public opinion monitoring reports are rich in data. The majority of their content is publicly available. And while their starting point is "to help officials understand public opinion and learn how to master it," it has been the recipient of a number of annual news and information awards from Southern Weekend and a number of other liberal media organizations as well.

In July 2011, the office's deputy director Zhu Huaxin came up with a new slogan: "Merging the spheres." It was referring to two spheres of public opinion -- official and unofficial -- that had formed with the constant marginalization of official voices on social media platforms. This division was unacceptable to China's leaders, so they had to take action to merge them into one sphere.

How did they do this? A number of specific measures were implemented over the next few years, which, as we all now know, yielded rapid results.

First, the central government in Beijing set up the Online Security and Informatization Leading Group, personally led by Xi Jinping. At its first meeting in February 2014 it pledged to clean up cyberspace. The clean-up operation started immediately, with the arrest of a group of the most active "Big V" Weibo users on charges of prostitution, tax evasion and defamation. Xue Manzi was a well-known example of these.

This "killing of the chickens to frighten the monkeys" had an immediate effect: a 40 percent decrease in the number of "Big V" Weibo posts during that year, according to the 2014 Analysis of Chinese Internet Public Opinion. Content on Weibo began to shift towards entertainment news and celebrity gossip. Major events and public intellectuals were no longer making the list of hot topics.

In August of the same year, the Central Leading Group for Comprehensive Deepening of Reform said it would strive to create several new mainstream media organizations. They were to use advanced methods and different formats to build competitiveness, communication capacity, credibility, and influence. The Paper was among them, as were Study Group and Xiake Island; new official, current affairs media using up-to-date language with fun nicknames. So on the one hand, they were killing chickens to frighten the monkeys, and on the other, they were starting to mold public opinion to their will.

That's how the spheres were merged.

There was another seemingly insignificant event that made me more keenly aware of the changes that were afoot.

The first emerged in the Chinese media industry around 2008. It was the Public Opinion Monitoring Office [later renamed the Public Opinion Data Center]. This agency had its roots in a magazine set up by the People's Daily titled "Policy Information," which was later renamed "Online Public Opinion." The tagline on the cover clearly stated its mission: "Helping senior officials to read the internet." Its editor-in-chief Zhu Huaxin was a communications scholar with in-depth experience in official media. He went on to become the deputy director of the Public Opinion Monitoring Office.

Zhu Huaxin, deputy director of Public Opinion Monitoring Office (Online Photo)

Zhu Huaxin, deputy director of Public Opinion Monitoring Office (Online Photo)

Back then, there were 250 million Chinese internet users; the largest number in the world. But there was also the emergence of Web 2.0 and social media, democratizing the online experience and giving everyone a voice. There was an explosion of online information, hot topics were being amplified, and mass incidents could happen and public opinions form about them in a very short space of time. For civil society, it was seen as a great opportunity to increase online presence and set the public opinion agenda around important events. China would be changed if everyone was watching, and the government would be forced to yield to the weight of public opinion.

But the government soon realized that the official voice was quickly losing its influence in social networks. No one wanted to read anything officially written. The government became the target of mockery, while market-oriented media organized already practiced at speaking to people in their own language and witty public intellectuals were the new rock stars of public opinion.

The government could see that this was a crisis, and so it decided that it would need to intervene to change the direction of online expression. And so the Public Opinion Monitoring Office dedicated to "helping senior officials read the internet" became an official think tank providing crucial analysis of public opinion and engineering solutions for government agencies at all levels.

Interestingly, their public opinion monitoring reports are rich in data. The majority of their content is publicly available. And while their starting point is "to help officials understand public opinion and learn how to master it," it has been the recipient of a number of annual news and information awards from Southern Weekend and a number of other liberal media organizations as well.

In July 2011, the office's deputy director Zhu Huaxin came up with a new slogan: "Merging the spheres." It was referring to two spheres of public opinion -- official and unofficial -- that had formed with the constant marginalization of official voices on social media platforms. This division was unacceptable to China's leaders, so they had to take action to merge them into one sphere.

How did they do this? A number of specific measures were implemented over the next few years, which, as we all now know, yielded rapid results.

First, the central government in Beijing set up the Online Security and Informatization Leading Group, personally led by Xi Jinping. At its first meeting in February 2014 it pledged to clean up cyberspace. The clean-up operation started immediately, with the arrest of a group of the most active "Big V" Weibo users on charges of prostitution, tax evasion and defamation. Xue Manzi was a well-known example of these.

This "killing of the chickens to frighten the monkeys" had an immediate effect: a 40 percent decrease in the number of "Big V" Weibo posts during that year, according to the 2014 Analysis of Chinese Internet Public Opinion. Content on Weibo began to shift towards entertainment news and celebrity gossip. Major events and public intellectuals were no longer making the list of hot topics.

In August of the same year, the Central Leading Group for Comprehensive Deepening of Reform said it would strive to create several new mainstream media organizations. They were to use advanced methods and different formats to build competitiveness, communication capacity, credibility, and influence. The Paper was among them, as were Study Group and Xiake Island; new official, current affairs media using up-to-date language with fun nicknames. So on the one hand, they were killing chickens to frighten the monkeys, and on the other, they were starting to mold public opinion to their will.

That's how the spheres were merged.

There was another seemingly insignificant event that made me more keenly aware of the changes that were afoot.

In July 2012, heavy rainfall in Beijing claimed 79 lives. There had been no torrential rains for decades, yet a lot of the deaths happened in city centers. Problems with infrastructure design shocked a lot of people, and sparked a good deal of online discussion. The Beijing municipal authorities were also getting pretty nervous.

After the rainstorm, a lot of media outlets went to investigate. One of them, Southern Weekend, found all the relatives of the deceased and published an eight-page feature titled "Your Names, Your Stories," containing a list of the names of all those who died and their personal stories. They planned to run it on the first few pages.

Back then, the official death toll had yet to be released. The day before publication, while the paper was already at the printers', the government banned the article, and raided the printing house to remove the offending eight pages. With the disappearance of the investigative report, the first few pages of the paper as it was seen by the public early the next morning consisted of nothing but hastily packed advertisements.

This is a classic example of censorship and withdrawal. But this was the age of Weibo. When the eight pages were done, the front page editor had already taken pictures and posted them on his very popular account. The order to withdraw the article, to censor those pages and to fill them with ads, wasn't issued until late that night. And it was broadcast live on Weibo by some members of the editorial team, where it caused a lot of outrage. The entire absurd process had been exposed, greatly reducing the effectiveness of the censorship.

But the story didn't end there. On the night of the gag order, I was watching the CCTV evening news as I always did. I noticed that the news anchors were all wearing black, and a special news broadcast was inserted into the program. One by one, the anchors read out a list of those who had died and a brief bio for each, wearing solemn expressions. The CCTV report won unprecedented praise. Many people regarded it as progress towards a more transparent government and the humanization of state media. The pages of Southern Weekend marked with the censors' red crosses were only circulated among small groups on Weibo, so their influence was limited.

Right then, it suddenly dawned on me that the rules of the game had changed. "Shut up" (the suppression of the truth) had become "Shut up and listen to me say what you just said."

If information control 1.0 takes as its primary aim the supervision and elimination of specific information and sources by controlling the truth-tellers, the truth doesn't get out. Then information control 2.0 takes the fight to the people, mass-producing new-era propaganda, winning fans, and mass brand recognition.

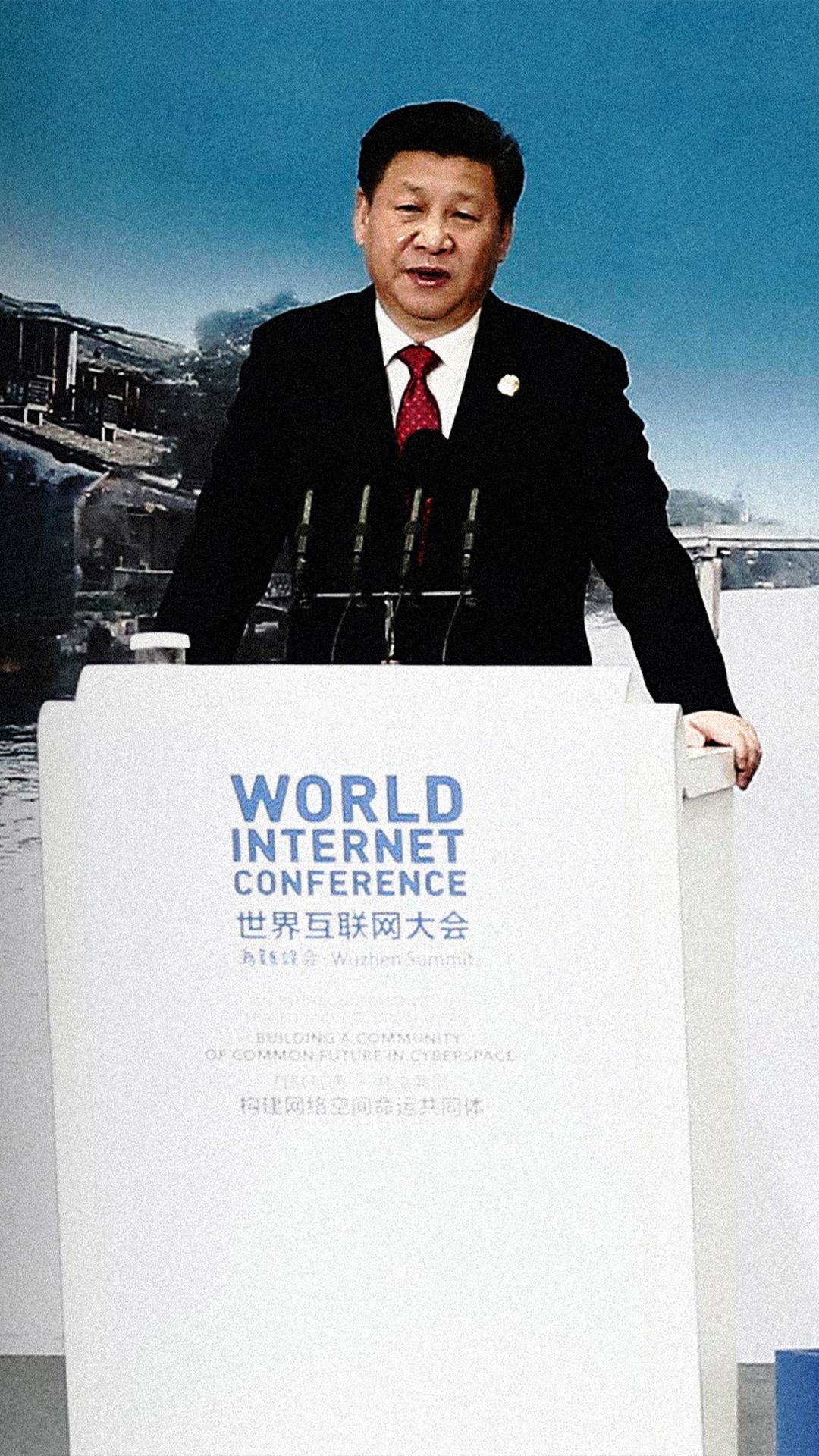

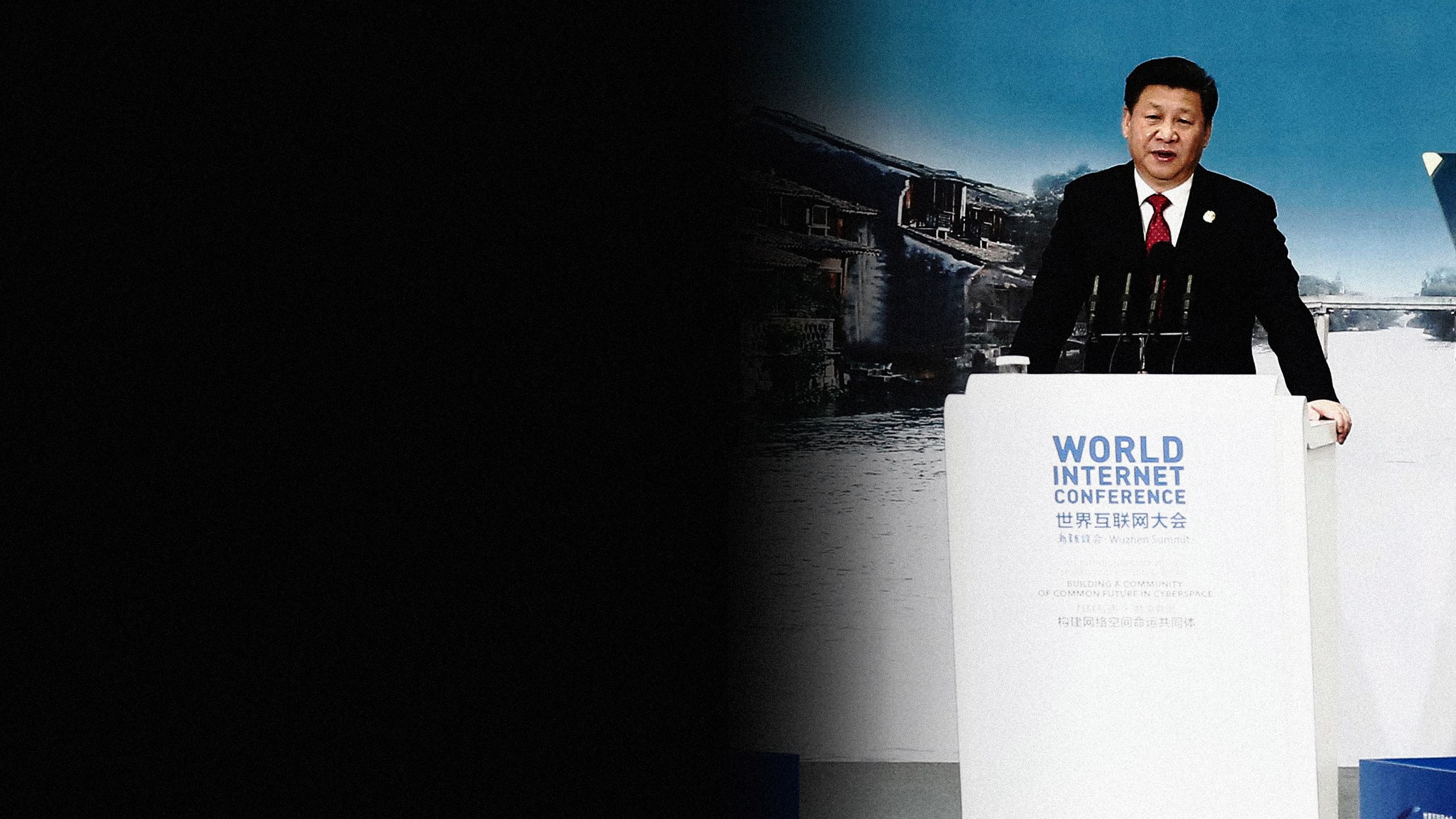

Photo: AP Photo / Mark Schiefelbein

Photo: AP Photo / Mark Schiefelbein

By 2015, three years after Zhu Huaxin had talked about "merging the spheres," the effects of these strategies have become clear. Accounts belonging to the People's Daily, Global Times and other official media have hired a large number of young people who use the language of today's internet to win these outlets the highest-ranking online followings and influence rankings. Meanwhile, in this war of resources, the rankings of the older, market-oriented media organizations have fallen out of the top 10, the top 20. They are being rapidly pushed to the margins.

Official opinion has stepped up the pace in recent years, regained the mainstream, and made the most of the available technology. It now wields far more influence than it did during the era of traditional media.

Around this time, I also spotted the emergence of another chapter in the story: information control 3.0.

2014 saw the emergence in Hong Kong of the Occupy Central campaign aimed at achieving the democratic universal suffrage promised in the Basic Law. The movement developed into the 79-day Umbrella movement. The movement became known for its peacefulness, rationality, and non-violent tactics. It was well-founded and reasonable, generating large amounts of news footage that touched the global audience, including some in mainland China. This caused quite a bit of anxiety for China's rulers.

Keen to stop these images of peaceful occupation and the fight for democracy from touching people's hearts, and keen to stop people from changing their minds about Hong Kong, China adopted an information strategy that was no longer just about blocking the truth, or spreading its own propaganda. Instead, it told huge lies to muddy the waters, hyped up the movement's flaws, stigmatized the fight for fully democratic elections as a bid for Hong Kong independence and peaceful marches as "Hong Kong's Cultural Revolution", or "color revolution". Calls for democracy were blamed on flaws in the economy, or a sense of fading superiority, magnifying the divide between mainland China and Hong Kong and stirring up resentment between them.

A senior journalist at a state media outlet told me back then that this was the largest information pollution campaign that he had seen since the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, and that it was largely orchestrated by state media organizations. The pollution campaign was hugely successful: a lot of lies were manufactured so that the truth couldn't be heard. And even if it did get heard, nobody would believe it.

Occupy Central with Love and Peace Movement (Photo: oclp.hk)

Occupy Central with Love and Peace Movement (Photo: oclp.hk)

After 2014, ordinary people in China believed that Hong Kong's economy was no longer as strong as mainland China, and that this had unbalanced the people of Hong Kong, so they began to make trouble, but that they needed the support of "overseas forces," the U.S. and the U.K., to achieve independence. Faced with this distortion of their peaceful demonstrations in China's state media, ordinary people in Hong Kong were left feeling cold and angry, as the divide between them and this abstract concept of China widened. They became less and less willing to distinguish between those who ruled China and its people; between China's government and Chinese culture. In the emotional war for hearts as well as minds, the truth isn't completely blocked, but it is greatly impeded.

The information control 3.0 strategy seen in 2014 reached new heights in 2019 when the protests in Hong Kong grew larger, more destructive and more disruptive. What was once a pollution campaign has gotten an upgrade. It is now a tactic ushering in an era of ongoing information war where public opinion is perpetually weaponized.

The era of information warfare was developing throughout the past decade of fine-tuning and upgrades to China's public information control systems and its growing dominance of public opinion.

The goal of information warfare is not to discredit a single target, but to make people believe nothing, and then to divide and polarize society, stirring up hatred and hostility, so that the foundations of democracy slowly crumble. The chief weapons of information warfare aren't bans, nor lies, nor censorship powered by artificial intelligence and other technologies. They are individuals; every single one of us who believes the lies, or who are angered or left indifferent by them. We are the chief weapons of the information wars: we and our loss of awareness.

Going back to the question I posed at the beginning: what is the most effective way for a dictator to deal with an influential dissident? It is to make us lose the capacity for independent and clear-headed judgement, and then to make us stop believing in our own values. All domination is based on this. And the seeds for revolutionary change are also hidden here, though they may be buried deep.

Background photos: AFP (Greg Baker, STR), AP (Ng Han Guan), The Paper