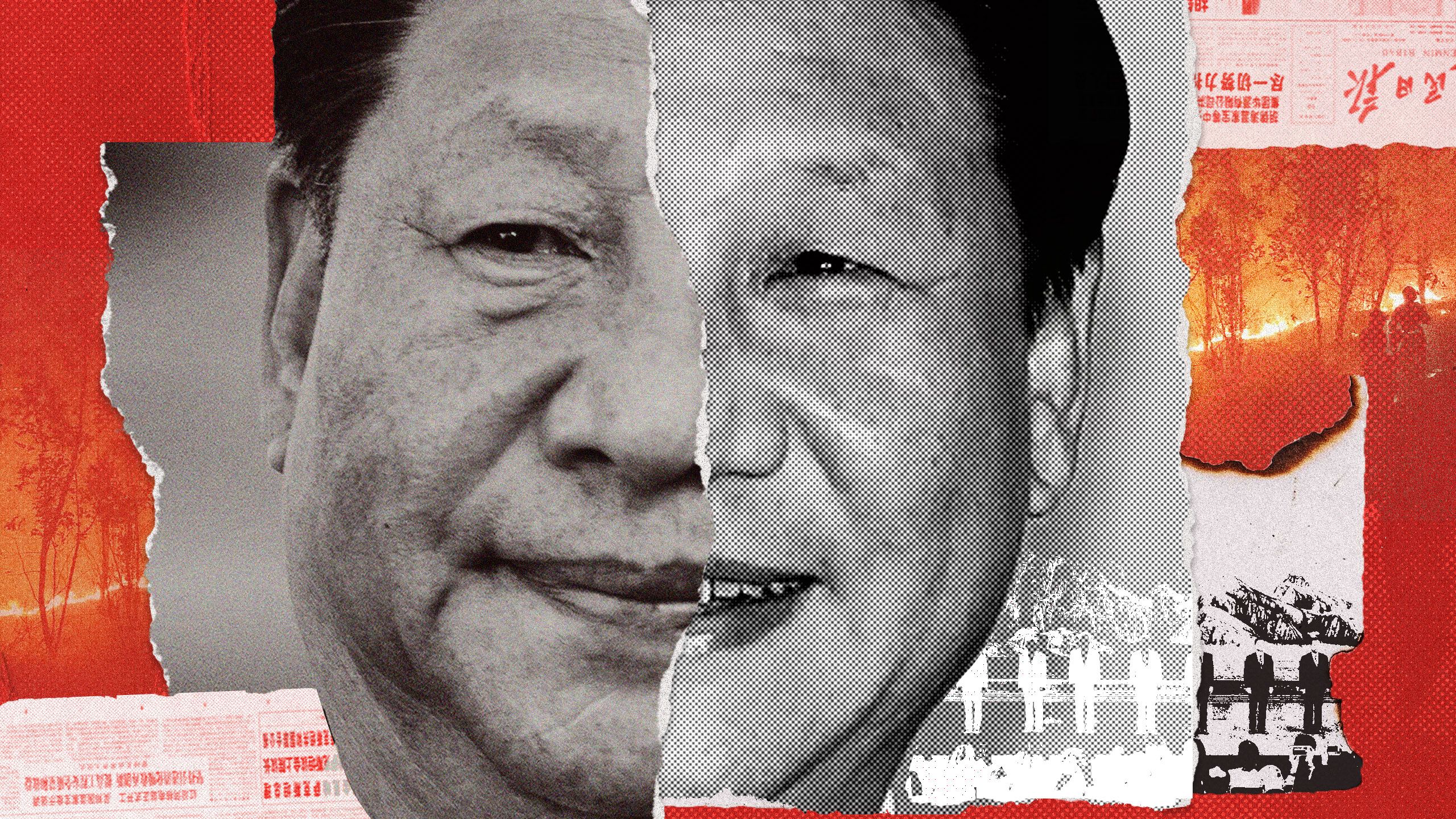

Behind the scenes in the Chinese Communist Party-controlled media

An Insider's Story

In 2016, Chinese president and Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping announced that the media belonged to the party and government, and exists to carry out its propaganda work. "The media is part of the party," he said, a phrase that became a catchphrase of the new era of politics under Xi. To be more specific, this meant that the media must "maintain a high degree of consistency with the views of the Central Committee," "correctly adhere to public opinion guidance work," and use positive propaganda to achieve stability and unity. The key phrase was "correctly adhere to the party's public opinion guidance work" where it applied to news.

While the overall increase in media controls and censorship was basically the same, regardless of whether an organization was in the private sector or an official party or state outlet, there were some differences in the way they were implemented, due to the differences between those types of organization. There is something of a siege mentality in state-run media at times. People on the outside may think those in state-run media have a good career, but actually that is a somewhat distorted view. Anyone who stays in the state news system will see their way of doing things and their outlook change drastically with time. Owing to numerous restrictions, regulations, tensions, and vested interests within the system, people inside this system rarely talk about it to those outside.

I worked in state media for nearly 10 years. I recently interviewed colleagues who work in party and municipal newspapers in the hope of describing the changes that have taken place in the media in the past few years, and what it's like to exist within that system today.

Lose "party-type" language, attract young people.

"Actually, a lot of my colleagues were looking for other job opportunities last year, but I'm going to carry on working here, partly because there is pressure on me to get married and have children, and partly because the pay and benefits as an editor on a party newspaper are pretty good," Li Ze tells me. "Then you have the coronavirus situation, so there isn't much staff turnover really. There really isn't much staff turnover at party newspapers, generally speaking."

After graduating from Renmin University in 2007 Li was assigned to a Chinese media organization. Soon after joining, he was made responsible for the entertainment beat, as well as party and government news in local provinces and cities. He tells me that working at a party newspaper has always been a political job. The benefits have always been good, so staff turnover is very low, and his department hasn't recruited anyone new for several years.

We start talking about changes that have taken place in party media organizations in the past few years. Presentation is the first thing that springs to Li Ze's mind. The concept of integrating content across different channels has truly taken hold. Even the print versions of party newspapers have taken on this way of doing things. Li Ze works for an organization that set up the multimedia centers across China under the support of the Central Propaganda Department, that include social media platforms like Weibo and WeChat among their clients. When Xi Jinping approved the text for the anniversary of one newspaper, the organization turned it into a comic strip -- not an obvious part of the newspaper's brand -- and published it in the comic book market.

Animation clips from Xi Jinping's Bo'ao Forum(Footage: The Paper)

Animation clips from Xi Jinping's Bo'ao Forum(Footage: The Paper)

Around this time, its journalists started doing vox pops on the streets and short lifestyle videos about hot topics, including topics like "What are your plans for after the pandemic?" and "Get the skinny on delicious eats" alongside a dedicated lifestyle service. The organization also began a lifestyle column for young people, in collaboration with the provincial-level Communist Party Youth Leagues. Even official news started to take on an interactive tone.

"The past few years have been all about losing party-type language from party publications," Li Ze says. CCTV's evening news show launched its WeChat official account and a column titled "The Anchor Speaks," in which a news anchor talks about one of the news stories of the day in one minute videos using colloquial language. Official media across the country soon followed suit with their own versions. According to Li Ze, official media has succeeded in grabbing the attention of a large number of young people in recent years. More of them are following the official accounts of media like Xinhua and the People's Daily, so the structural changes have been hugely successful.

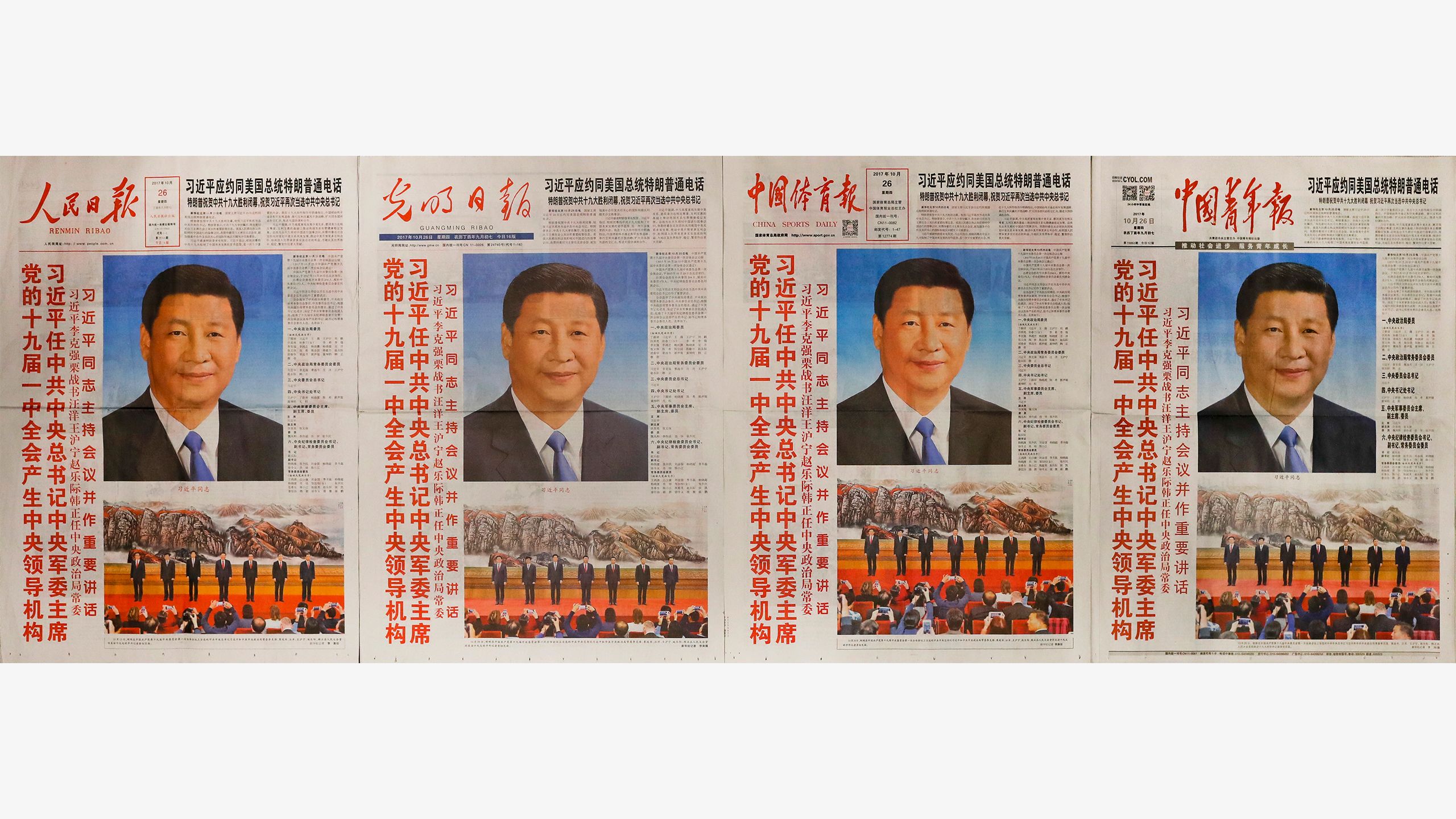

The Central Propaganda Department sees all.

"Maybe everyone does think that the party newspaper is just a party mouthpiece, and that propaganda is consistent across the board," says Li Ze. "But actually there have been huge changes in the past few years." But not everyone outside the state media system will necessarily understand how that happened, he says. "For example, there are no strict rules [in official regional papers] about what can appear as a front page lead story," he says. "It could be an economic story, or local news from whichever city." But party newspapers must lead with stories about the central leadership, wherever they are, he says. For example, a meeting of the Politburo, or a speech given by General Secretary Xi Jinping would definitely need to go on the front page. Another change is the requirement that local stories about local government policies, or news about specific provinces and cities, must now be approved by the propaganda department of the province they are in, which wasn't previously necessary. Editors of publications are only able to approve public opinion "supervision-type" content that generally focuses on areas in which public-facing government departments have performed poorly, and other aspects of the people's livelihood.

The most striking change for Li Ze has been the reduction of space dedicated to news reports about the central government and provincial party committee meetings. Previously, Xinhua’s itinerary of official activities for the central leadership was published as syndicated content, and relied upon by all media. But the central propaganda department doesn't have obvious control over color pieces linked to such events. "If you compared the reports from different provinces back then, you would see that the Nanfang Daily in Guangdong and the Liberation Daily in Shanghai would file separate features that were suited to their different styles," Li says.

But all of that changed after Xi Jinping's inspection visit to Xinhua back in 2018. Li Ze’s newspaper sent reporters to the stops on the leaders' itinerary to write up a feature. But the reporters sent on that assignment say that the paper was suddenly told not to write it. Later, Li Ze found out that this had been on the orders of the central propaganda department. Instead, media was to use syndicated Xinhua copy only for the visit, with no changes, not even to the headline.

"This meant that our jobs were about to get a whole lot easier," Li Ze said. In 2018, the propaganda department of the Shandong provincial party committee has stipulated that all reporting on provincial and municipal-level meetings must use official syndicated copy, with minimal editing. The byline of the writer is to be added alongside the name of the local reporter, where requested by the issuing agency. This saves local reporters a lot of time and effort.

Li says: "The layer-by-layer approval process at party newspapers has definitely been strengthened in recent years." But he admits that he had no say in the matter. "Before, I was able to use my skills when covering meetings. Now, I just use the pre-written copy as required by the regulations. I don't know how I feel about that.” There has also been a sharp increase in the number of political study groups Li Ze must attend at his party newspaper, he says. There are also many more sessions devoted to the study of the party spirit.

Reporters don't report; the tips line no longer rings.

"I can still stay here at a city newspaper, but that has little to do with any ideas about reporting the news," Li says. "It's just a way to make money, to earn a living. "Some newspapers have started selling property, or even sea cucumbers. The journalists have got to do something, because the newspapers they work at have nothing to do now," A Qiang, a reporter at a city newspaper, tells me. "What else are they supposed to do?" City newspapers are different from party newspapers. They are supposed to offer a general news and information package to a readership in a given city. Unlike official party media, they are run like private businesses. A Qiang says the last few years have been a bit of a roller-coaster, but, sadly, one in which he has gotten stuck at the bottom.

He was proud to have gotten hired by a well-known investigative paper on graduating from journalism school. He worked there for six years. The newspaper specialized in exposing shady stories and investigative reporting from all walks of life. A number of major corporations were placed in its spotlight, and it was very well-known back in the day.

But the investigative paper was wrapped up last year, so A Qiang was sent off to work at a different city paper as manager of the advertising department, a middle-ranking leadership position. A Qiang also runs a social media account commenting on the real estate market, in addition to his main salary from the newspaper. He also writes some soft features on the side for developers to earn extra cash. A Qiang says he once was an idealistic journalist, but times have changed. "You can have all the ideals you like, but reality is what it comes down to. It's better to do something realistic," he says.

But he still misses the days when he did undercover investigations. Reports emerged at the end of April that a reporter investigating the deaths of four children was beaten up in Yuanyang, Henan province, causing some public concern. A Qiang felt for the reporter, especially regarding one detail of the story. "The official report from the local government talked about a stubborn journalist, as if the guy was dumb or something, but that's quite an accolade for us investigative reporters," he tells me. A Qiang has never seen himself as a white collar type, but it is precisely his rather rough appearance that enabled him to infiltrate different environments, collecting information while working in restaurants and kitchens, or selling real estate, or dressing up as a migrant worker to pay visits to construction companies. There are many more instances.

But city newspapers are only allowed to write about less sensitive topics these days. "Comparing the daily hotline tip-offs is very telling. Seven or eight years ago, a tip-line at the newspaper could expect to get more than a dozen good tips a day," A Qiang says. "If we had followed all of them up, we could have filled the newspaper several times over." "There was a much broader range of stories, for example, we could even write about rights activism and even grassroots conflicts with local officials," he says. "We were so motivated back then, coming into the industry at that time, so alert for every lead."

"Now, we have seen a huge decline both in the number of leads we get and in the number of sources they come from," A Qiang says. "In the past, we had a dedicated hotline department, which was specifically responsible for tip-offs and emergency helplines. That department has now been merged with something else, and we're not allowed now to do original reporting of fast-breaking news anyway."

The decline in the number of hotlines is understandable if journalists are feeling the pressure from higher up, and are no longer allowed to follow up leads, nor to write based on news values. Eventually, there won't be any more breaking news, and nobody will trust the media to write the truth any more. I have first-hand experience of this.

Footage: AFP TV

Footage: AFP TV

Back when I had just graduated and was hired as a reporter by a provincial newspaper, I would chase stories and write them up based on their news value. When I had been in the job about a year, something unexpected happened. I got a tip-off that there had been a melee in a technical-vocational college over a young woman who had been involved in an inappropriate relationship with a teacher at the school.

Just as I was about to start talking to an injured student, I got a call from my editor telling me the story was no longer needed, and to return to base immediately. At the time, I didn’t understand the unwritten "rules," and I imagined that if I just dug deeper, I might win praise and approval, so I ignored this instruction and went ahead with the interview. I was looking forward to writing up what I had gotten in the interview, but instead I got a huge dressing down, because the school had contacted the propaganda department, which had told us to stop pursuing the story. The newspaper tried to talk to the college about it, but my unauthorized actions had affected the ability of my colleagues covering the education beat to do their jobs, and I got a warning and "a very serious mistake" added to my record.

This made me keenly aware that any newspaper has its own big boss behind the scenes: the propaganda department, and of the tangle of vested interests linking college, newspaper and propaganda department.

Several years later, my former boss and I discussed this incident again, when both of us had already left the paper concerned. He told me that my dedication to the story was an example of how a journalist should be, but that it was accepted procedure for a media organization to beat that kind of enthusiasm out of any new recruit.

Banned from reporting a local forest fire.

In late April of this year, a forest fire broke out in A Qiang's area. The general feeling in the past was that the paper should definitely send someone, regardless of whether the copy would ever see the light of day. But now, "nobody cared about the fire except for some of the older reporters who posted a few reports from citizen journalists and other media to their circle of friends on WeChat," he says. "The Propaganda Department banned any local media from reporting on the fire, saying that they must use officially sanctioned copy from Xinhua and party newspapers instead," A Qiang tells me. A Qiang tried searching for media reports about the blaze. The "Beijing News" and "Red Star News" reported some details of the fire. "The People's Daily, Weibo and CCTV issued official reports about the fire, but only party newspapers reported the story locally, in the form of an inspection by the municipal party secretary. Pretty much all of the other local media were silent on the story," he says. "This is not just a local thing: it's a nationwide trend," A Qiang says helplessly.

"During the pandemic, for example, a lot of city newspapers from different provinces sent reporters to Wuhan to do their own interviews, but then the Central Propaganda Department organized more than 300 journalists to write syndicated official copy instead," he says. "All that journalists need to know is this: they have to tell the China story well," A Qiang says. He says there are plenty who are willing to oblige. Last year, for example, he hosted a journalism student intern who was far keener on the [nationalistic] Global Times than the [more cutting-edge] Beijing News or Southern Weekend.

The Global Times

The Global Times

"After the investigative paper folded, we had colleagues drafted in who were directly responsible for doing propaganda work for specific government departments," A Qiang says. "That includes writing and running the official social media accounts of government departments and public opinion guidance work relating to news stories. This has led to a very interesting phenomenon: journalists stationed inside government departments, so that their press releases were penned by our colleagues, which was more than a little bizarre."

A Qiang finds his current job easy, but boring. He asks me to help him by downloading the newspaper’s app. He said it something he always did when meeting new friends, because the newspaper had set a hard target of at least 2,000 new registrations a year for the app. By the end of April, he has only 700 completed. "It makes my head spin just thinking about it," A Qiang says.

As for me, after I made my "serious mistake," I gradually got used to having my copy spiked, and toed the line at work. Later, I joined an in-depth investigation department specializing in undercover investigations. It did sterling work for an evening newspaper, but the entire department was laid off with the strengthening of media controls in 2015, and I resigned. At that point, a lot of journalists started leaving the profession and finding other work. Some went into public relations, others took the civil service entrance exams. Some even opened noodle restaurants. Some people in the industry said we journalists were "molly-coddled. "

But journalism is actually a dangerous profession in mainland China. Throughout my career I have seen investigative reporters lose their jobs or even their freedom, one after another. This has been because of something they wrote or did that ran afoul of the powers-that-be. Mainland Chinese journalists are unlucky in one respect, because they have to navigate various forms of censorship. But they are also lucky, because they are able to take the measure of the current regime because of the dealings they have with that censorship. It, too, is a record of our era.

(The names of the interviewees have been replaced with pseudonyms.)

Background photos and video footage: Reuters (Stringer), AP, AFP TV