After the fall of China's internet czar

What happened to the independent media?

On Feb. 29, 2020, Assistant professor Fang Kecheng of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) was recording a podcast on media representations of the coronavirus pandemic. Halfway through, the other people on the show realized that Fang wasn't saying anything, and thought the internet connection had gone down.

Fang Kecheng had just heard that that the NewsLab account he'd been running on WeChat since 2013 had been shut down.

More than 300 of his posts had disappeared from WeChat, leaving only the announcement: "Due to complaints, this account has been blocked, and the contents are no longer available to view. This account is suspected of violating administrative regulations on the running of public internet accounts."

"Going back to last year at the very least, the rules of the game for online content have changed," Fang says, adding: "It is no longer possible to protect ourselves."

"There are nationalist 'little pinks' who use their words and actions online much as any young militant in the Red Guards would have done: anyone can be silenced once they target and report them," Fang says.

"People who are serious about the content they produce face increasing levels of risk, because there are no longer any basic principles at all," he says.

After the fall of the internet czar

China ranks 177 out of 180 countries in the 2019 press freedom rankings published by the Paris-based press freedom group Reporters Without Borders.

It has long been the case that Chinese media outlets are all also official media outlets. Former senior editor at Netease’s news channel Wen Yunchao said in his opinion piece, that the so-called independent media first appeared as underground newspapers after the Cultural Revolution. But they fell silent after the military crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protests on June 4, 1989.

"The emergence of independent media once more became possible with the advent of the internet," Wen says, citing blogs, websites and e-zines like the China Public Opinion Survey, Douban's Strawberry Weekly and Love Date, as well independently funded private and quasi-official print publications.

All of these have now been placed under tight controls.

Former Southern Weekend reporter Zhai Minglei's Minjian, its website, along with ONENews, have been totally shut down.

In 2009, with the launch of Weibo, a new breed of "Big V" social media stars emerged, putting a slight dent in the official media's monopoly on discourse.

More space for independent media opened up with the launch of WeChat in 2012. But some people were also being targeted: Lu Yuyu, founder of Not The News, was sentenced to four years in prison for "using the internet to pick quarrels and stir up trouble" after he carried out investigations into mass incidents and published details in various places.

In 2016, Lu Wei, commonly known as China's internet czar, was removed from his post as director of the powerful Cyberspace Administration, investigated, and eventually sentenced to 14 years in prison, marking the end of an era. Since then, however, there has been no let-up in online censorship. In fact, things have gotten worse.

In March 2019, Wall Street News was investigated, fined, and ordered to "rectify." But it was taken down eventually anyway.

The following month, the photographic image site Visual China was closed for "rectification" for one month. It was ordered to rectify again in December that year.

In October 2019, the video and news platform Vice China ceased operations.

And in November, the news site Toutiao was ordered to rectify and "improve its content."

In March 2020, the team behind Jiemian's NoonStory was disbanded.

……

Li Haipeng's ONELab, Horizon, NoonStory, Tencent's Guyu project and other sites, were also fined, then lost their edge and their influence. "Non-fiction writing was booming just a few years ago, but it is pretty much gone now," laments a former editor of one of these sites.

It wasn't just that there was too much content with little commercial scope: the government was afraid that somebody was start writing the truth. So the government tightened the screws even on non-news copy. There was nowhere left to go.

In 2009, with the launch of Weibo, a new breed of "Big V" social media stars emerged, putting a slight dent in the official media's monopoly on discourse.

More space for independent media opened up with the launch of WeChat in 2012. But some people were also being targeted: Lu Yuyu, founder of Not The News, was sentenced to four years in prison for "using the internet to pick quarrels and stir up trouble" after he carried out investigations into mass incidents and published details in various places.

In 2016, Lu Wei, commonly known as China's internet czar, was removed from his post as director of the powerful Cyberspace Administration, investigated, and eventually sentenced to 14 years in prison, marking the end of an era. Since then, however, there has been no let-up in online censorship. In fact, things have gotten worse.

In March 2019, Wall Street News was investigated, fined, and ordered to "rectify." But it was taken down eventually anyway.

The following month, the photographic image site Visual China was closed for "rectification" for one month. It was ordered to rectify again in December that year.

In October 2019, the video and news platform Vice China ceased operations.

And in November, the news site Toutiao was ordered to rectify and "improve its content."

In March 2020, the team behind Jiemian’s NoonStory was disbanded.

……

Li Haipeng's ONELab, Horizon, NoonStory, Tencent's Guyu project and other sites, were also fined, then lost their edge and their influence. "Non-fiction writing was booming just a few years ago, but it is pretty much gone now," laments a former editor of one of these sites. It wasn't just that there was too much content with little commercial scope: the government was afraid that somebody was start writing the truth. So the government tightened the screws even on non-news copy. There was nowhere left to go.

NewsLab shut down

NewsLab shut down

Fang Kecheng relaunched his NewsLab on Facebook in May. The first lecture on media and social development in mainland China was taught by him. The assignment centered around Archaeology, a mainland Chinese website that had been shut down.

The same fate would soon befall NewsLab itself.

On Jan. 10, a WeChat post by the YouthAssemble (Qingnian Dayuan) website opined: "Without the Australian wildfires, I would never have known how powerful China was 33 years ago." It was retweeted by the ruling Chinese Communist Party official newspaper, the People's Daily, and went viral. "Refuting this kind of anti-narrative is a duty," Fang says. He posted in response: "I'm sorry, but we shouldn't sing the praises of [the government's handling of the] wildfires 33 years ago." Fang cited a China Youth Daily report from the time, and hit out at YouthAssemble for inciting nationalistic sentiment and distorting history. But his post was deleted, and the original post carried on spreading through the Chinese internet.

Chinese internet users found comments Fang had written on Facebook and accused him of supporting independence for Hong Kong. Three days before Fang's WeChat account was shut down, YouthAssemble posted that Fang's account was a "newcomer that had been banned from Weibo and Bilibili for supporting Hong Kong independence. The person behind the account is Fang Kecheng, and we think he will get blocked pretty soon."

"It was pretty obvious from the way they wrote it that this was the organization that reported me," Fang says. "There are considerable vested interests involved here, and maybe I trod on somebody's toes."

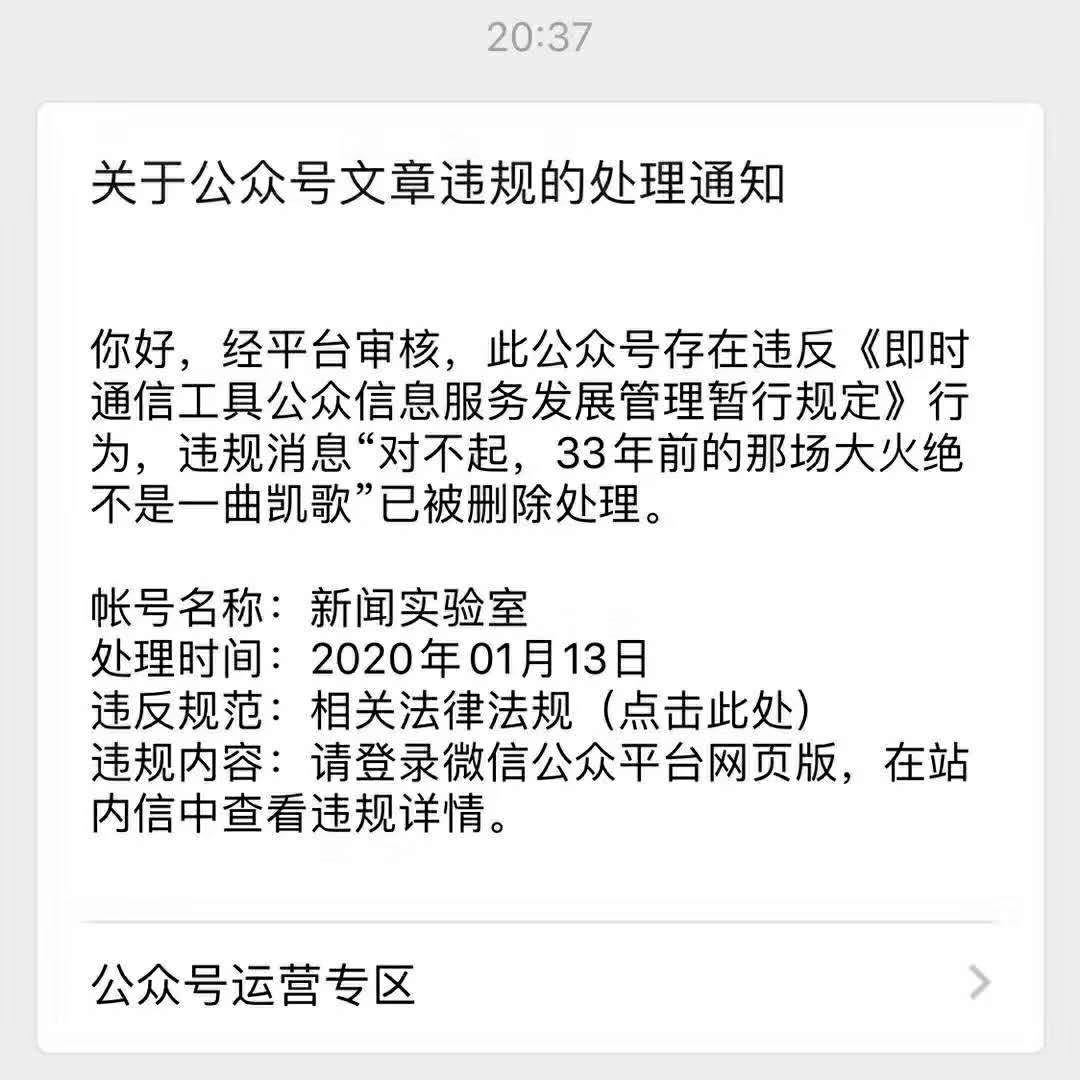

NewsLab's shut down notice screenshot

NewsLab's shut down notice screenshot

"I didn't think it would get shut down by the platform itself, because NewsLab brought traffic and content to WeChat," Fang says. "But they must have gotten a directive from the Cyberspace Administration."

People lamented that even such a soft-spoken moderate as Fang would get shut down. But Fang himself admits that his reputation as a moderate came from self-censorship. He was just better at figuring out where the red lines were before, he says.

The loss of Curiosity

The loss of Curiosity

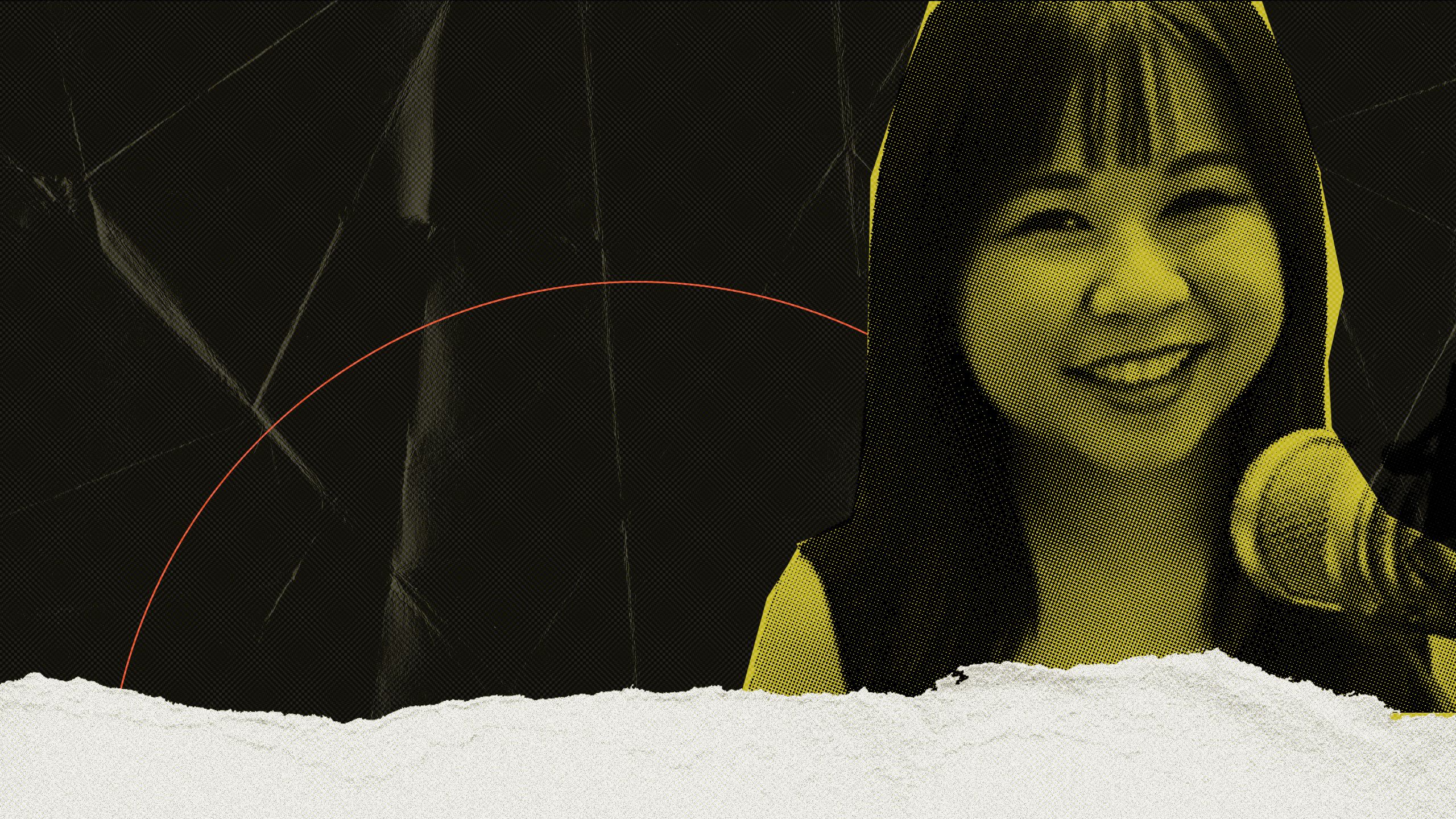

The head office of the Curiosity Daily was in an old, three-story house on Fuxing Middle Road in Shanghai. One afternoon in July 2018, it was raided by about 30 people, comprised of officials from the city's Cyberspace Administration, cultural law enforcers and a few uniformed police officers.

Reporter Chen Liya was the only employee from Taiwan there. At the time of the raid, she was in the editorial office on the second floor. The intruders ordered her and her colleagues to stop working immediately, not to touch the computers and to hand over their phones. Chen Liya and several of her mainland Chinese colleagues protested that the officials and officers had no search warrant.

To which the reply came: "You know who we are. What do we need a warrant for?"

Then they herded all of the staff into the conference room. One of them had some sheets of A4, possible evidence of "criminal activity." They had two articles printed out in very large, thick font, according to Chen. She says the two articles weren't considered sensitive enough to have triggered the raid, but the two authors were interviewed as part of the investigation anyway. She also heard one of the raiders say into their phone: "These people really won't play ball!"

"I knew that there were controls on free speech in China, but I really hadn't expected to encounter something like this," Chen says. For Chen, who was born in Taiwan after the lifting of martial law and the end of the authoritarian Kuomintang (KMT) regime, the incident recalled the white terror of Taiwan's own past.

Later, the Shanghai Cyberspace Administration issued a document saying it had received online tipoffs that the company behind the Curiosity Daily had illegally set up a news operation and editorial team, provided news and current affairs content in violation of regulations, ran original news copy, and published a large number of articles on current affairs and politics from the foreign media.

The Curiosity Daily announced it would be suspending operations for one month to undergo "rectification." Its app was removed from stores, and the entire platform ground to a halt. Some articles were also deleted.

This wasn't the first time Chen Liya had had her work deleted. Her most short-lived report -- about Peking University student, #MeToo whistle blower and labor activist Yue Xin -- only existed online for 36 minutes. Articles about a lack of support for Putin's constant "re-election" by younger people in Russia, the 50th anniversary of the 1968 Student Games in Europe, the 10th anniversary of Shanghai Pride, the beating of a Beijing security guard, a gender transition service center in Guangzhou, and the shutting down of the Feminist Voices Weibo account, also got deleted -- or "harmonized," Chen recalls. Chen also remembers being detained by police and chased out of a court building; none of which would have happened in contemporary Taiwan.

Screenshot from Yue Xin's twitter account

Screenshot from Yue Xin's twitter account

(via AP Photo / Pavel Golovkin)

(via AP Photo / Pavel Golovkin)

1968 Student Games in Europe(via AP Photo)

1968 Student Games in Europe(via AP Photo)

Shanghai Pride (via Retuers / Nir Elias)

Shanghai Pride (via Retuers / Nir Elias)

The 798 incident–women beaten at Beijing's 798 Art District (via RFA)

The 798 incident–women beaten at Beijing's 798 Art District (via RFA)

In an article about her experiences titled "When a 404 is an everyday thing", Chen wrote: "The first few times my copy was spiked, I wept quietly in front of my computer screen, out of an indescribable feeling of disgust. I asked a colleague once, out of a sudden feeling of anxiety: "Will I just get numb eventually?"

But she never did. "The next time I had an article spiked, I still felt sad," Chen says.

The Curiosity Daily was founded in 2014 by Yi Xianfeng, one of the founders of the digital financial newspaper CBNWeekly. The following year, Chen was hired as its Taiwan correspondent. Two years later, she moved to take up an unfamiliar role in Shanghai, and joined the organization as a formal employee.

Back then, the lack of formal accreditation wasn't a huge problem, as there were ways to report without it.

Curiosity Daily started out as a business paper, because people thought that business could solve social problems, Chen says. But things started to mature in a changing social environment to include more of a focus on government policy. "There was no way to avoid the impact of government policies on businesses," Chen says.

By 2018 the Curiosity Daily had more than one million subscribers. Someone referred to it as "China's most profitable business magazine."

But then came the raid, and the subsequent "rectification" by the relevant departments. Now, the content of the website has shifted. They can't touch on anything sensitive, and the stories are mostly lifestyle features about people in the news. The experience left Chen with a lot of trauma. She still kept doing her job with the same energy, and writing her stories, but eventually she grew bored and listless. She eventually resigned and went back to Taiwan in March of the following year.

She went back to Shanghai on a visit in June, at which point the Curiosity Daily's suspension was extended to three months. Advertising revenue was hit hard as the paper's Weibo and WeChat accounts were suspended and all of its apps deleted from stores. The day she visited her old office, Chen witnessed first-hand an employee meeting during which 70 or 80 people were forced to take redundancy. Only around a dozen now remained.

Some colleagues went to work for other media organizations. Some changed careers altogether. Nowadays, Chen Liya will occasionally visit the website. But only the big company news seems to get updated these days. The only articles are written by the last of Chen's colleagues; two or three people who are working on a part-time, partly voluntary basis.

Like a wound that can't be covered up, a banner in the upper right-hand corner of the site reads: "Reporting Violations." It was placed there as part of the "rectification" process.

NGOCN shut down

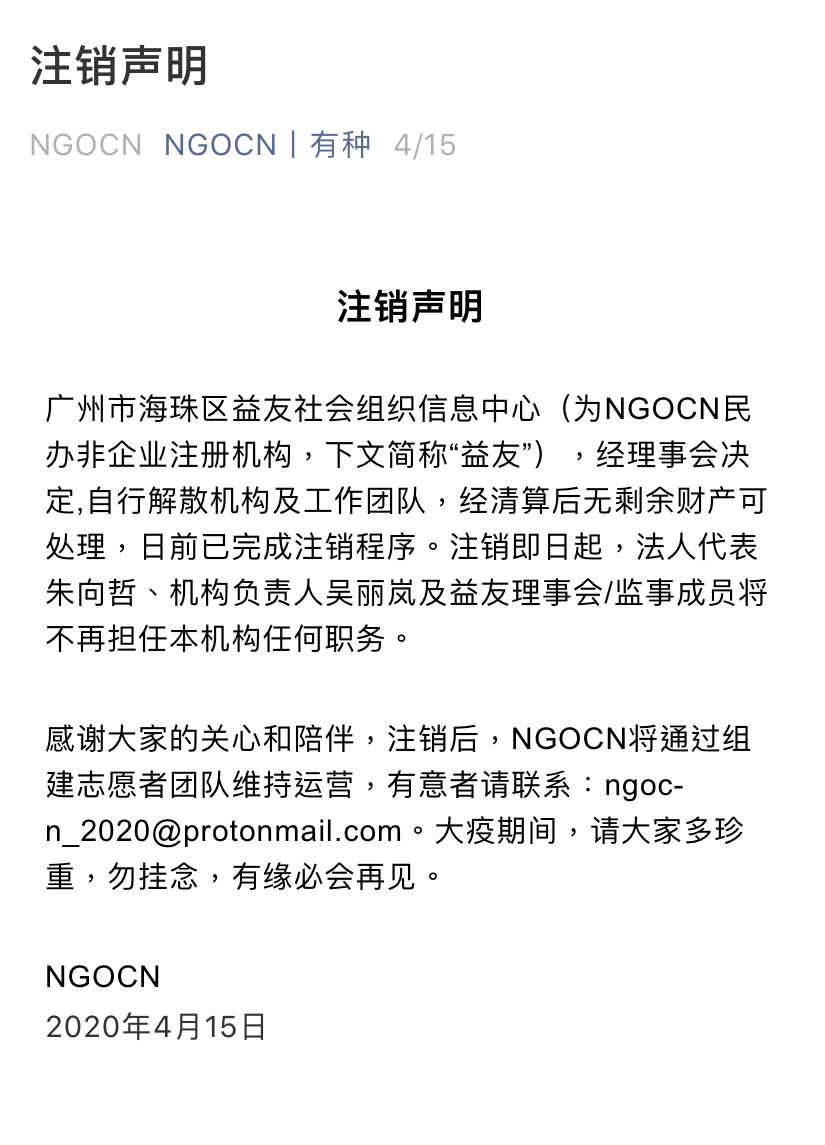

The NGOCN Daily used to have new content every day, uploaded by volunteers. But in April, its parent entity, the Guangzhou Yiyou Social Organization Information Center was the subject of a deregistration action by the authorities. This non-governmental organization, which had operated as an independent media organization since 2014, was shut down after 15 years of operation.

The NGOCN Daily's shut down statement (via WeChat)

The NGOCN Daily's shut down statement (via WeChat)

The warning signs were there as early as June 2018.

Every time NGOCN applied to have its license extended, its application was rejected by the Civil Affairs Bureau. Meanwhile, its bank account was frozen. So the organization took the Civil Affairs Bureau to court.

Former NGOCN team member An An says that the court refused to accept the lawsuit, however.

"The person in charge was also harassed many times, and was asked to 'drink tea' with the authorities," An An says. "This created a lot of pressure on the team and also affected the editorial side of the operation."

NGOCN, with its "action changes lives" slogan, had gradually morphed from an online information platform to an independent media organization, with the flourishing of the new media sector in China. Its team of writers was kept small to avoid the issues linked to the lack of official media accreditation, and their business cards described them only as editors.

But they still broke a lot of news before the mainstream media did, including early stories about the #MeToo movement in China. In the case of the CRISPR babies, whose genes were edited in an attempt to confer immunity to HIV, they were the first to dig up the informed consent agreements from the official website of the institute in question.

But they were constantly targeted and harassed by ruling Chinese Communist Party officials. "At least 5 NGOCN WeChat accounts have been blocked," An An says. "At its peak, our Weibo had 100,000 followers," he says. "It would get shut down and then go back up to 30,000 or 40,000 followers again. The last time, we only got to 10,000 followers before it got shut down again."

"We're pretty proud of the reporting we did," he says. "But not so much of the work we produced later [after rectification]."

The original idea had been to make NGOCN as influential as possible, so it would be harder for the relevant departments to go after it. But that's not how it turned out. "Maybe we didn't get big enough, quick enough," An An says. "I always think things might have turned out differently. This wasn't a happy ending," he says.

A scattering of stars

The war on independent media in China was also waged on individual social media influencers. Wuhan writer Fang Fang felt the pain of this keenly after the coronavirus emerged in that city. Her Lockdown Diary had already had several entries deleted. But then she was overwhelmed with online threats and abuse after she started to prepare the diary for publication as a book in English. The wave of hate also engulfed Liang Yanping, a professor at Hunan University, and Wang Xiaoni, a retired professor at Hainan University, both of whom expressed support for Fang Fang. They were subjected to investigation by their universities, and their accounts on Weibo shut down.

Wuhan writer Fang Fang. (Photo: CNS)

Wuhan writer Fang Fang. (Photo: CNS)

Even media that makes money hasn’t been spared. In February 2019, the authorities shut down the Weibo and WeChat accounts of Talent Limited Youth -- the brainchild of mega-platform MiMeng -- after it published an article titled "The death of a humble-born champion." The Beijing News and The Paper -- formerly cutting-edge publications -- applauded the move.

Mimeng, a mega-platform on WeChat. (Online photo)

Mimeng, a mega-platform on WeChat. (Online photo)

But Fang Kecheng doesn't agree with them. "As long as there are enough people to keep reporting, the government will continue to intervene and ban things. But such an approach will promote populism," he says. He says the fact that some organizations have stayed out of reach, while others have been targeted is "the highest expression of nationalism."

He says the war on independent media has hurt public discourse and the creative industry. "I always wanted a wider audience for my work, but the practise of informing has made a lot of people very nervous," Fang says. "Now, we are less likely to let people outside of our immediate bubble see what we write, so they can't report us. But this is also bad for public discourse."

Chen Liya went back to Taiwan, where she was hired by Initium Media. She has since filed a number of influential reports for them from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China.

Fang Kecheng continues to teach in Hong Kong. Copies of his WeChat posts are available outside the Great Firewall of Chinese internet censorship. They can only be viewed by those in mainland China with circumvention tools, or sent to followers who leave their e-mail address. His Reading the Foreign Media paid course is now on hold.

Fang makes light of the crackdown for himself, noting that in working alone he is not bringing collective punishment on others, as he would be if he were working for a newspaper. "I'm just a single person; but if it were the case of something like The Wall Street News, the entire company could be affected," he says.

NGOCN's editorial team have each gone their separate ways, doing their own thing, but have been hard to track down during the pandemic. "Some enrolled in college, some switched to research, some are still freelancers, and some have gone over to traditional media organizations," says An An. "We need to make a living, at the end of the day, and we need to protect ourselves first and foremost, given the current climate," he says.

Guo Yijie, one of the disbanded NoonStory team, wrote an article looking back on the past five years. At the end, he quotes Taiwanese writer Tang Nuo. "Everything that is beautiful, even the truth, can so easily be suppressed and subjected to persecution. But the most moving thing of all is that it will never disappear forever."

"History shows us, again and again, that [beauty and truth] will always return, maybe in a different time or place, or among a different people, rolling in like the waves on the ocean, until they happen upon the right kind of soil for their growth and survival."

(The names of the interviewees have been replaced with pseudonyms.)

Background photo: Chen Liya, NGOCN web photo